News

16 May 2019

The Politics of Wireless

Subscribe to CX E-News

WIRELESS

The Politics of Wireless

by Simon Byrne.

Recently I was intrigued to see a post on the Live Sound Engineers Facebook page complaining that a major venue would not free up some wireless frequencies, so as to permit a freelance audio recordist to record a gig in that venue for a podcast.

The implication being that the venue had the right to dictate what frequencies could, and could not be used, and this amounted to restriction of trade because the audio recordist could not confidently do his job because he could not guarantee that his wireless gear would be on clean frequencies.

This is wrong on several levels!

No person has any more rights to the class licenced spectrum that we use than anyone else. The restriction of trade allegation is an entirely different matter which I’ll get to later.

Wireless microphones in Australia operate under the Radiocommunications (Low Interference Potential Devices) Class Licence 2015 (as varied in 2018).

That means the users or the devices themselves are not licenced, but the category of equipment has an overall licence. Therefore manufacturers design the equipment to meet the specifications of the LIPD class licence such as transmission frequency, effective radiated power, modulation type, and so on.

If equipment meets the requirements of the licence, it automatically qualifies for use under the licence.

Users of the LIPD class licenced devices are bound by the rules set out in the licence. As LIPD class users don’t have to pay fees to use the spectrum, they operate on a ‘no interference’ and ‘no protection’ basis. As you can see, a LIPD class licence is the simplest form of licence which affords users very little rights.

Users must ensure that their devices don’t cause interference to other radiocommunications devices in the vicinity. They also have no protection from interference or changes that may affect them. The concept is that they are low power devices and therefore the risk of causing interference to others is also low.

Works great, unless you have a lot of devices such as wireless microphones in one venue!

Unless users are specifically licenced (which can be done for major events), ACMA takes a dim view of people claiming that they have exclusive rights to some of the spectrum. That is completely against the goals of a LIPD class licence. The objective of the licence is to maximise the amount of low power users in an area, with the minimum amount of administration.

Wireless spectrum is an extremely valuable and finite resource. The live event industry is just one small category of user of wireless spectrum (and we are small in the scheme of things), that has extreme and ever increasing demands on it.

By way of comparison, the new 5G cellular phone technologies are forced to operate at extremely high frequencies (about 20 Ghz) because there are no other large amounts of spectrum available. Because of the extremely high frequencies, their wavelengths are extremely short which means they have very poor propagation.

This is forcing the phone companies to put in as many as four times as many cells as compared to 4G to get adequate coverage. That would be hideously expensive.

As the use of technology such as drones and autonomous vehicles evolves, increased wireless internet and mobile communications usage will make wireless spectrum even more valuable. More devices are competing for less spectrum.

It is right that we are encouraged to manage our use of it in an efficient way and we should not feel hard done by. It is after all, free for us to use.

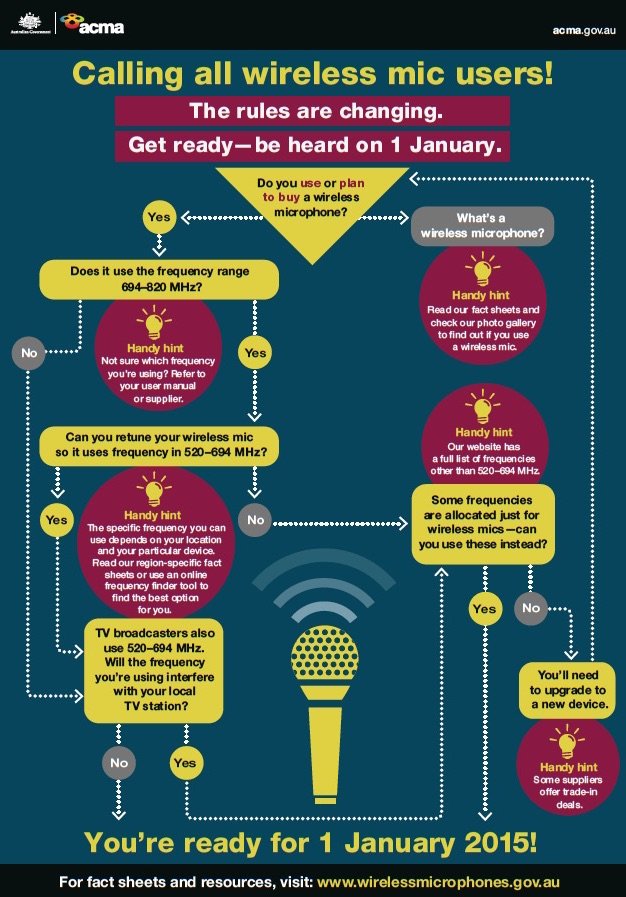

Infographic from ACMA

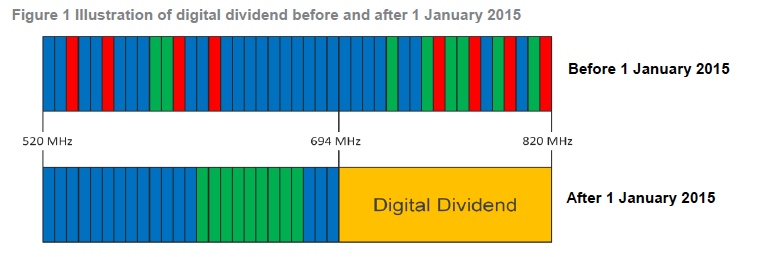

For background, things are much worse in the United States as they are well established on their second round of spectrum buy-back, this time from the television stations who are getting out of free-to-air television broadcasting. In many markets, this will force US wireless users to once again buy new systems as their frequencies get restacked even more.

As for the restriction of trade claims that prevent outside audiovisual contractors coming into venues, I’m afraid that horse bolted years ago.

If a client signs a room hire contract with a venue that contains a clause stating that they will use the in house provider, or that the venue may place restrictions on outside contractors, it ends there because that is what the client has accepted in writing. That is, the venue hirer has agreed to the audiovisual supplier restrictions as part of the contract as a whole.

A comparable, but equally poor argument would be hiring a full service venue, but wanting to bring your own food because you can buy it cheaper, rather than purchasing the venue’s more expensive offerings.

The venue has an agreement in place to say no, so it doesn’t fly. This is why on the last ENTECH Roadshow, Julius paid for some outrageously expensive sandwiches!

The venue hire client is entitled to negotiate audiovisual (and sandwich) issues prior to signing the contract (and some clients do), or take their event to another venue where they can use their own audiovisual suppliers on better terms. As much as it displeases the independent audiovisual suppliers, there is no restraint of trade here.

However, should a venue permit external audiovisual suppliers in, it has no rights that are backed by law to dictate what frequencies they can or cannot use under a LIPD class licence. The licence is very clear; all users operate on a ‘no interference’ and ‘no protection’ basis and no person has greater rights than any others, and in Australia, a venue cannot contract out common law.

Having said that, it makes sense that the operator of the most wireless devices in a building, the in-house provider, takes responsibility for coordinating the use of the available spectrum within those walls.

In my view, as part of a house frequency allocation plan, venues should allocate a dozen or so spare and permanent frequencies to be available to visiting contractors. When an outside audiovisual supplier comes into the venue, they are simply handed a list of available frequencies. Then both the venue, and the outside provider can be confident that their use of wireless devices will not cause problems for the other party.

I’ve only ever had one instance where a venue representative has tried to stop me using wireless microphones on the basis of potential frequency conflict. I politely told him that under the law they had no basis to stop their use, and that we needed to work together.

I then gave him a list of frequencies that I planned to use and advised him that it would be a great shame if I had to explain to my client that in the event of wireless interference, it was a direct consequence of the venue refusing to work with us to ensure that we do not interfere with each other.

Unsurprisingly, a solution was worked out.

Get on people! Available spectrum is going to get tighter and planning will become even more important.

CX Magazine – May 2019 – Australia and New Zealand’s only publication dedicated to entertainment technology news and issues – available in print and online. Read all editions for free or search our archive www.cxnetwork.com.au

© CX Media

Lead image courtesy Joel Sulman, FB post: “Asked for a stage plot for an event… gave me their wireless mic and this post it note…”

Further reading from CX Magazine’s Wireless Feature – May 2019:

Shure Reveal Twinplex. Mission: Take on DPA – by Julius Grafton

Wireless Voodoo – Not a Dark Art – by Fraser Walker

In-Ear Monitoring – by Sennheiser’s Adam Karolewski

Clear-Com FreeSpeak II – by The P.A. People’s Chris Dodds

Signal Out of the Noise – by Simon Byrne

Is that a wireless intercom in your pocket? – by Jand’s Jeff MacKenzie

Antennas for Wireless Microphones – by Jand’s Jeff MacKenzie

The Politics of Wireless – by Simon Byrne

Wireless Recordings – by Andy Stewart

From the archive – Wireless Mics were a feature in Connections Magazine, March 1999:

Radio Microphones (Sub-titled “How Did I Get Stuck With This Job!”) by John Matheson (includes a wireless systems Buyers Guide and Radio Spectrum Guide for Australia.)

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.