News

26 Apr 2022

Blindness: Binaural Audio, Scary AF

Subscribe to CX E-News

(Photos by Saige Prime)

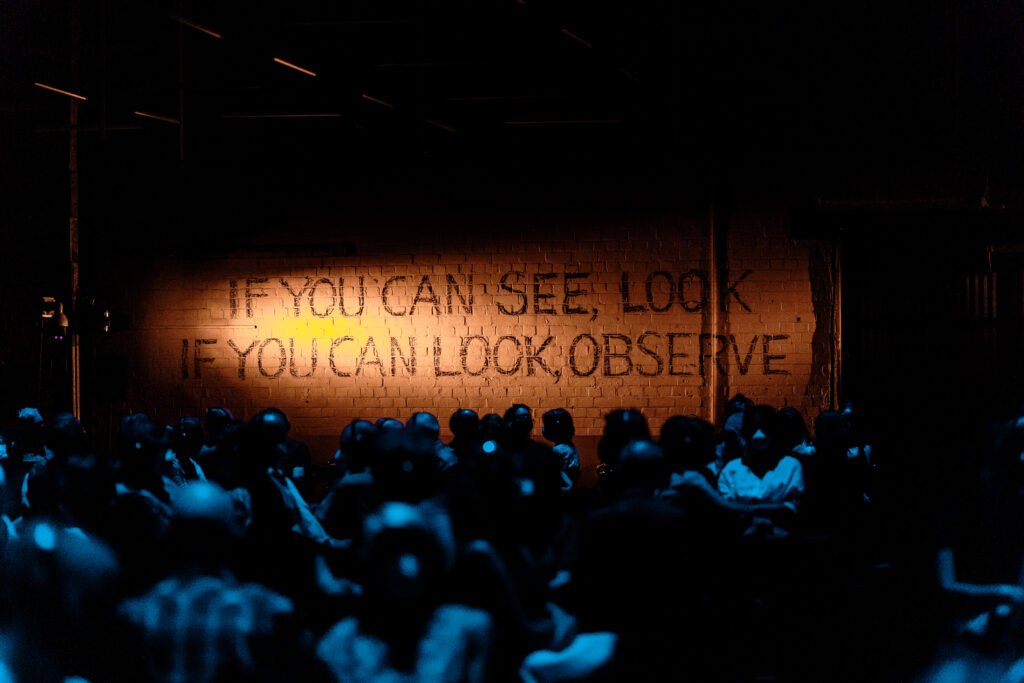

Adelaide Festival have really embraced their edginess over the last couple of iterations, with the ‘AF’ logo plastered all over town. It’s confronting, as was the Donmar Warehouse’s acclaimed UK production Blindness, which I experienced (enjoyed is NOT the right word) in the hauntingly decayed space of The Queens Theatre in the centre of Adelaide’s CBD. Presented by Arts Projects Australia, locals Novatech provided the production infrastructure, including lighting, rigging, audio, vision, and control.

Based on the 1995 novel by Portuguese author José Saramago, Blindness is the story of a pandemic. One that sends an entire city blind. Society collapses. Very, very bad things happen. It’s like Squid Game meets Contagion. There are warnings on the door about content before you walk in. They are justified.

All of this might be considered a little ho-hum if you’re used to confrontational theatre, but here’s the interesting thing about the show; there are no live actors. The entire production is a narration performed by British actor Juliet Stevenson, recorded binaurally, and played back to the audience via headphones. Most of it occurs, naturally, in full blackout.

After two years of boring my wife with my ‘There will be no significant pandemic art! Shakespeare hardly mentioned the Black Plague! No one’s interested!’ speech, I was proven pretty spectacularly wrong. Blindness is not only about a pandemic, everything about the way it physically functions is because of a pandemic. The audience are physically segregated and can sit on chairs next to each other if they’re from the same household. We were all wearing masks. There are no actors sweating or breathing at you. The headphones the audience wear are supplied in double quantity because as one set is used, the other set is being disinfected backstage.

The show is structured in three acts, which are defined in the amazing sound design by Ben and Max Ringham. We open with some background story, and the narration in your head is being played back in simple stereo. Marking the end of the first section and the beginning of things going very wrong indeed, the Wahlberg DMX-controlled winches move, the LED tubes come down in bright white to just at eye height to encase you in a hellish prison, and everything goes dark. The narration then switches to binaural and it’s like the actor is actually sitting next to you, or moving around the space, or, most realistically, whispering in your ear. You feel like you would actually touch her if you reached out. The adjective ‘disturbing’ doesn’t do the effect justice.

Like another tech I talked to about the show, I often found myself concentrating on how the show was functioning technically to distract myself from the actual content. I think if I’d been an average punter with no idea how these effects were created, I might have ended up foetal on the floor.

The real genius in the sound design is accepting the limitations of the equipment and the medium, and then working around them. The first artistic choice is the pairing of the actor and the headphones. The original Donmar Warehouse production in London used ‘Silent Disco’ headphones rented from a specialist company. They can receive three stereo channels, which allows for the binaural mix, an audio described version, and two mono summed channels. Using the same tech in Adelaide, these are not high quality studio headphones. But you only ever hear a female voice through them, and there’s basically nothing going on under 250Hz. This makes the most of the spatial effect.

The headphone narration is supported by sound effects, ambience, and music that runs through a surround system encircling the audience. The Adelaide production utilised an L-Acoustics system of eight X8s around the audience perimeter, two X15 HIQs flown above, two SB18 subs and two SB218 subs, plus two 112P powered 12”s at the dock door. This system does all the heavy lifting in the lower frequencies and creates a viscerally perceptible aural environment outside the headphones. Especially for the gunshots and explosions.

Jessica Hung Han Yun’s lighting design is more art installation than theatre piece. The 113 Colordreamer LED tubes on winches fly in, fly out, take on different shapes, blind you, lead you, and threaten you. The lighting rig, which also includes 50 ETC Source 4 LED Lustrs, 14 Kupo cyc floods, four Selecon Arena Frenels, and an LED strobe, is run off an ETC Gio 4K. The DMX controlled winches are run by a separate High End Systems HedgeHog 4N.

At the heart of the whole production, a Novatech OneSystem Constellation rack (a gig-in-box we wrote about back in CX171 in July 2021) houses the computer that’s running QLab for show playback, the video system that monitors the four infrared cameras around the audience for safety, processes and distributes the audio via a Yamaha TF Rack, and triggers the lighting system via MIDI.

In the end, we’re led back into the light through the dock doors. The audience on the day I attended shuffled out in silence. Everyone has some kind of PTSD caused by COVID, especially in our industry. A show like Blindness, running in the middle of a major arts festival, is part of a healing process. As we get back to work making art, we’re reminded that one of its main aims is to help us make sense of and process our experiences. Especially the traumatic ones.

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.