Listen Here

12 Aug 2022

Listen Here: Mixes That Punch

Subscribe to CX E-News

Do you ever feel like your mixes lack power and punch? Maybe they start out with plenty, but eventually wind up sounding flatter than a freeway. If this sounds like a predicament you’ve faced more than once, you’re not alone. This article is specifically for engineers striving to preserve the punch in their mixes right through to the final master.

There’s nothing worse than realising, just before you’re ready to print a mix, that the punch from a song’s rhythm section has vanished like the mirage off a hot road. Only now, when you’ve armed play/record on your favourite mixdown device, have you suddenly realised that the snare is nowhere, or the kick sounds like an insipid pillow strike.

Have you been asleep at the wheel these last six hours or has this catastrophic change been a slow drift away from your mix fundamentals while you’ve inevitably focussed on other things?

It’s the latter to some degree, typically, although there are usually other processes at play here that have slowly chipped away at your punch and dynamics without you being fully conscious of it. Occasionally, as a mix develops, you can misread how best to present the dynamic elements of the track, hammering them with compression early on, only to later realise they would have been better off with none at all. Did you try the drums without compression, or did you just apply your default mixdown mentality; “Must compress the drums! Must compress the drums!”?

It’s a frustrating feeling when you suddenly realise that the ‘punch’ of your mix has taken a leave of absence. Here’s a few ways to combat its disappearance.

The Master Bus

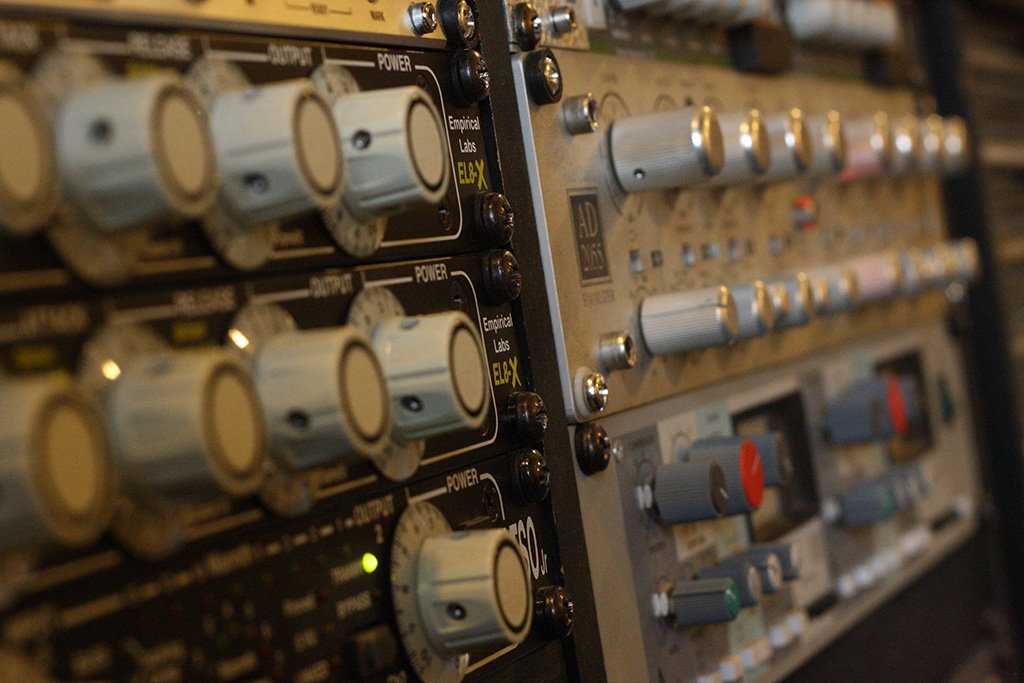

Starting with the crudest, most influential control measures we might have in place, often the master bus compressor contributes to a severe lack of dynamics and punch if it’s set incorrectly or ignored for hours. Typically it’s hidden from view 95% of the time, which doesn’t help!

It might be working too hard (harder perhaps than when you first set the parameters), be set to attack your signal too quickly, release too slowly, or even be the wrong compressor for the task at hand (they’re all a bit different). When a mix bus compressor is any of these things it can easily rob your mix of punch and life.

The quick remedy here is to bypass the bus compressor, temporarily releasing your mix from its ham-fisted clutches. If the song explodes back into life, then great. You’ve found the cause of the problem and can make moves to resolve it: adjust the settings afresh so the unit’s no longer clobbering the audio, or maybe even ditch it altogether.

The same logic applies if you have a limiter or multiband limiter/compressor in the mix bus chain. Limiters in particular can annihilate your dynamics. Impactful sounds like kicks and snares more so than virtually any other element. These signals are fundamentally about the transients. Take that aspect of the sound away with a limiter, and you’re effectively just turning these instruments down. Maybe this is your problem.

Channel Compressors, Limiters & Sidechains

Individual sounds on individual channels or groups can suffer a similar fate during mixdown, although here more specifically, the loss of punch might be worse. While mix bus compressors can sometimes make a mess of transients, they typically do so by turning everything down. In extreme cases your whole mix may be forced to ‘duck’ as the kick and snare, for example, push the rest of the instruments down as one. Although, in an ironic twist of logic here, ducking of this type can serve as a sonic weapon if used with care and specific intent. Slightly overcooked kick and snare levels will trigger a mix bus compressor to push the other instruments back just enough to allow the driving drums to dominate the soundstage. Used incorrectly, however, and the drums themselves will be flushed down the same toilet as the rest of the instruments.

On individual tracks, too much control can quickly smother the impact of a sound, particularly if it’s a fundamental component of a song, like a kick drum or snare. When these are held back too much on their individual channels or subgroups, they can quickly be reduced to wallpaper. That’s okay if your preference is for these elements to behave as such, but if you’d prefer them to sound like they’re tearing through said wallpaper with punch and attitude, then perhaps not!

Often it’s a delicate dance between these two types of dynamics control. Some channel compression (but not too much) combined with some action on the mix bus (but not too much); that works best. Just don’t forget to keep asking yourself the simple question: ‘Why am I compressing these drums so much if I want them to punch?’

Then there’s a third process; sidechaining a sound (or group of sounds) to which you might add more extreme levels of compression and distortion. By choosing to create a bombastic sidechain mix of, say, drums and bass, putting these elements through a more severe compressor/limiter and returning this signal back into the mixer, you can add aggression, excitement, power and ‘attitude’ to your mix without adding too many wild dynamics. Sidechaining punchy elements and controlling them heavily with compression (the beneficial side-effect of which is distortion) allows you to increase the apparent density, as it were, of things like drums, creating the perception that they’re stronger, louder, more consistent and vivid, without them increasing substantially in volume. By sidechaining your punchy dynamic elements, you get them to pop and project more attitude, whilst making the overall mix flatter and less dynamic. This is particularly important if you want to drive very small speakers whilst preventing them from clapping out under the weight of too much dynamic.

Phase… Again!

Another great robber of dynamics is phase. Indeed, if it’s severe, a phase issue is almost guaranteed to turn the dynamic, percussive elements of your mix into, harsh, thin, impotent and often strangely inconsistent sounding garbage.

The science behind this is simply the action of sound waves combining to partially or fully cancel, rather than reinforce, one another, thus reducing their amplitude and therefore impact. Particularly with drums (although phase problems are by no means restricted to this complex instrument alone – almost anything can exhibit or develop phase problems), multiple mics can wreak havoc with the power and punch of a drum sound.

With acoustic drum kits in particular, always check for phase: every time you add an effect, include extra mics, add reverbs, or induce phase incoherence with EQs and compressors, taking particular care to make sure your DAW’s delay compensation is on and working the way it should. Make sure, for example, that the power of your kick and snare sounds aren’t undermined by out-of-phase overheads. If things go soft, or thin, or lack vitality the moment you turn the overheads up, you have a phase problem that needs rectifying. The same goes for every other mic on the kit. Test each additional mic to make sure it’s reinforcing the fundamental power of the whole kit, not just of the drum it’s closest to.

Leave Some Things Alone!

One of the more straightforward ways to preserve the punch in your mixes is to leave some of the instruments alone, particularly in respect of their dynamics! Sometimes mix engineers get thoroughly carried away with trying to control ever single element of a mix to the eventual demise of a song’s overall dynamic push and pull, by almost literally stopping the arrangement’s capacity to breathe. Mix engineers (and I’d include mastering engineers here) can sometimes undermine a song’s natural highlights by fighting against every moment that pops, dominates or exaggerates the arrangement. Let’s not forget something vital here folks; songs live for those moments! Snuff them out with compression and severe limiting at every juncture and you may just consign the song to the scrap heap.

Mix Order & Fader Levels

Lastly, if a lack of punch and power is something you suspect your mixes suffer from habitually, rather than occasionally, then maybe other issues are at play here. Assuming you don’t have an undiagnosed technical issue in your system, perhaps it’s time to rethink (or reimagine) your process. Two obvious suggestions I have here in this regard are 1: Try working on things in a different order of mix priority, and 2: Learn to push your levels around far more with an ear for experimentation.

With regard to point 1; far too many people work a mix from left to right, with little or no thought given to why, and the vast majority of these engineers have the kick drum on Channel 1. Why? No-one remembers…

If you’re in this category, don’t be insulted, and certainly don’t despair. When you establish your drum sounds first, either out of habit or ritual, their punch and volume can often be overtaken by other instruments later. Like a runner who leads early in a race, looks the goods but then gets swamped in the home straight, your drum tracks shine early but are overrun towards the end of the race. If you want your drums to punch and sound less like wallpaper by the end of proceedings, consider working on them last!

Regarding point two: faders are the quickest way to turn something up that’s drifted into obscurity. Don’t be afraid to push faders around… like a little brother. Too many engineers get progressively more gun-shy about moving faders around too much once a mix starts to take shape. Bollocks to that. Get your hands on some faders and go nuts with them, particularly if the mix feels lacklustre. Don’t play balances safe all the time, intellectualising their relative levels like a scientific doctrine. You’re at the helm, steer the course you want to take without fear or favour. You won’t hit rocks, but you may just rock!

Andy Stewart owns and operates The Mill studio in Victoria, a world-class production, mixing and mastering facility. He’s happy to respond to any pleas for pro audio help… contact him at: andy@themill.net.au or visit: www.themillstudio.com.au

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.