DISRUPTIVE

17 Nov 2022

NICK SCHLIEPER’S LIGHTING for STC’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Subscribe to CX E-News

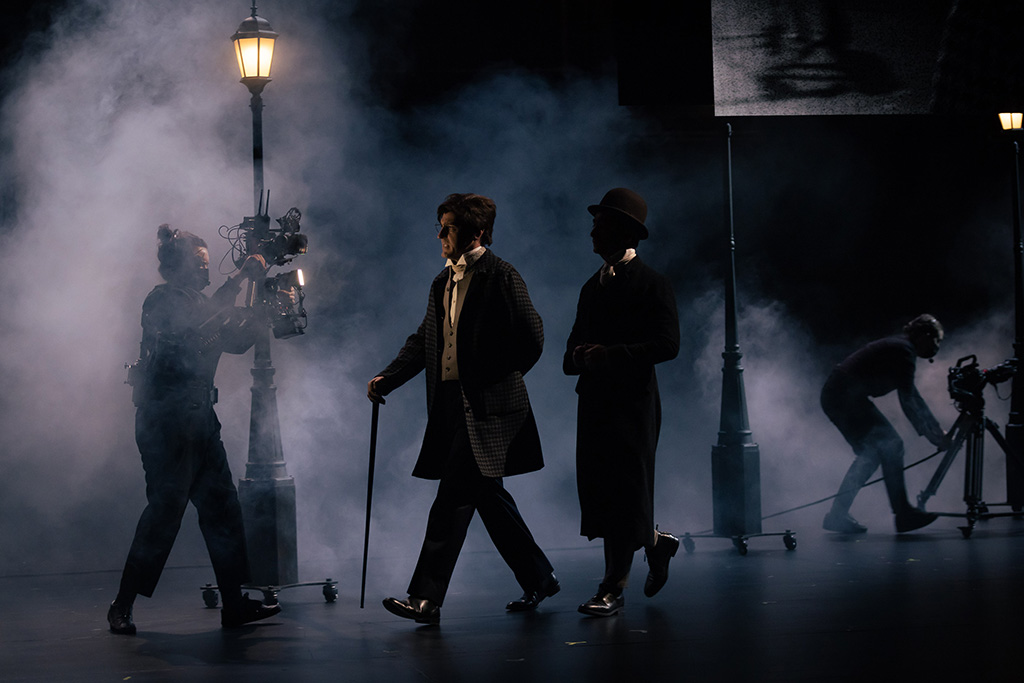

The Kip Williams’ adapted and directed Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, from the 1886 novella by Robert Louis Stevenson, took the technical lessons learned from 2020’s The Picture of Dorian Grey and applied them to a darker, much more tightly controlled canvas.

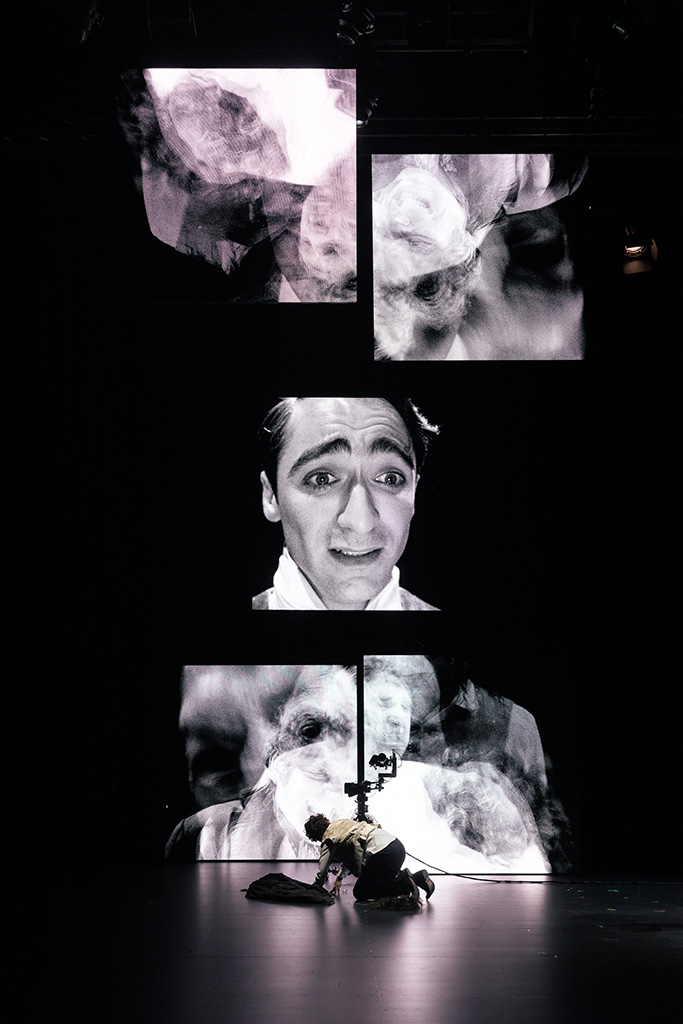

STC artistic director Kip Williams calls his technique of integrating multiple live cameras, LED screens and pre-recorded video into live performance “cine theatre”, and it’s an apt description. Dorian Gray used the technique to dizzying effect as Eryn Jean Norvill played all characters in the work, acting against recorded versions of herself. The aesthetic of the production changed as the story progressed, employing multiple styles and looks.

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde uses the same technical principles, but is aesthetically anchored in a firmly noir look. An even more precise and controlled production sees actors Matthew Backer and Ewen Leslie hitting hundreds of marks with absolute precision, allowing for unbelievably accurate shots and interactions with video. An extremely faithful adaptation of the original work, it is a dark exploration of the good and bad within everyone, which comes as surprise after a century of much lighter interpretations in popular culture.

CX Interviewed Nick Schlieper about the artistic and technical challenges posed by screens, cameras, dense dialogue, and making a 19th century text relevant today.

CX: Had you had worked with Kip Williams’ screens and cameras many times before?

Yes, but not many. I have done a lot of shows with Kip, but I didn’t do Suddenly Last Summer, which is one of the first shows where he used video in a big way. I did do The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, which had one screen only, but a lot of cameras and a very large screen that was the back wall of the stage. What I can say is ‘thank god for the LED screen’. Having spent a career keeping light off of very sensitive projection screens, you couldn’t even begin to contemplate doing shows like Dorian or Jekyll and Hyde with anything else but LED screens; it just wouldn’t be feasible.

The obvious difficulty comes in lighting for the cameras and the live audience simultaneously. The kind of light the camera likes is the quintessential opposite to the kind of light that I like seeing on a stage. I’m always turning the contrast up, and cameras hate that. Then you throw in the fact that the camera never stops moving, so you’re lighting everybody at 360 degrees. And you’re still sitting in a theatre watching it. It’s not like anyone is expecting or indeed wanting TV studio-quality lighting, where every single light source has a soft box on the front of it. You’ve still got to produce images that look striking and heightened on the screen and the stage. I don’t think we were entirely successful in that respect in Dorian, but were much more so in Jekyll. Of course, the black and white aesthetic of the show helps enormously there.

CX: Jekyll and Hyde has a consistent noir aesthetic. I see Bergman films and black and white 1970s Hammer Horror films. What were the aesthetic touchstones of that look?

It draws on one of my longstanding sources of inspiration, which is German silent movies of the 1920s. For me it goes right back to 1920’s The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in 1927. That world, that’s my personal touchstone. That aesthetic extends right through to the 1940s in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Third Man. I re-watched Citizen Kane just before we went into rehearsals and I’m sure there’s moments somewhere in Jekyll and Hyde that, at the very least subconsciously, are very reminiscent.

CX: You’re fairly restrained in terms of light sources in Jekyll and Hyde. Is there a certain consistency to the fixtures?

It’s a case of horses for courses. The rig is full of Martin MAC Encores. That colour temperature is perfect for treading the very fine line between lighting the show properly and not putting a black and white image on stage, which obviously you can’t do anyway. It’s not the first time in the history of theatre that people have tried to produce something that, within its constraints, reads as black and white. That was one of the things I was most unsure about; how much colour I was going to get away with before it was fighting with the twin image on the screen?

That said, I didn’t find it all that scary, because the colour palette I mostly work with is just shades of white and grey. There are a few notable exceptions to that, but that’s my usual colour territory. A lot of the time I’m using the Encores without any colour in them at all. It’s the perfect tool for this situation. The other reason I used them, and I used them on Dorian for the same reason, is because they’re quiet. Once you start putting upwards of 40 moving fixtures in the rig in a great big empty, echoey, potentially boomy stage with no masking, it really becomes a factor.

We all know what happens when you go to a break in a musical and the room goes quiet, only it doesn’t, just a massive heaving beast of a thing up in the roof going ‘jg jg jg jg’. You can’t do that under these circumstances and the performers are, if anything, just as mic’d as they would be in a musical. You’ve got a pair of very live microphones walking around even when there’s only one person on the stage.

CX: How much is the use of moving lights dictated by the fact you have to work around moving LED screens?

LED screens are much easier to work with than projection, and are much more forgiving. But you still can’t hit an LED screen directly with light; they’re not that forgiving. I did this exercise for the future of Jekyll, should it tour; there’s a 100-odd presets and just under 400 individual focuses. Now that’s nothing in terms of a musical, but a hell of a lot for a play that doesn’t even quite run two hours. It’s very fiddly and an awful lot of those shots are literally head shots. They’re doing five, seven seconds worth of stage time for one particular closeup on a camera and then they’re gone and never used again. It makes those shows pretty difficult to pick up and tour quickly.

Then there’s the fact that there’s no fixed set. The premise is that it’s always an empty theatre space. We positioned bits of scenery in the model, and we worked with the markup in the rehearsal room, but when you start out at the beginning, comparatively speaking, it’s open slather where anything is going to end up and you couldn’t do it without a lot of moving lights.

CX: I really noticed in Dorian the absolute precision of where anybody had to be at a given time, to the millimetre in some cases, and it was obvious before the show started just how many spikes there were on the stage. I didn’t notice that to the same extent in Jekyll. I imagine it’s just as precise, but you seem to have hidden it a little bit better.

It is. I think part of the reason you’re more aware of it in Dorian is because it was only Eryn Jean on stage. The fact of the matter is that there’s more than 200 spike marks in Dorian and well over 300 in Jekyll. Part of that is because there are so many more pieces of scenery in Jekyll, so they’re not all camera or performer marks. In Jekyll, there’s a pattern of going from super-specific moments, where both actors have one toe on one mark, one other toe on another, and then one or both of them breaks out and roams freely around all over the stage.

That’s the reason I used camera mounted lights so much more in Jekyll, because I didn’t want to compromise the stage picture by lighting what would sometimes have been the entire stage, but only for 40 seconds only. It seemed a bit of an inevitability that I was going to need to follow them, rather than compromise the entire stage image all the time.

It seemed more true to the aesthetic of this production that the camera operator that’s shadowing the actor also has this Cyclops eye that keeps interrogating that actor as they move. The other option would have been putting another 3000 cues into the show and following them around stage with the rig, but it would look awful and take way too long!

CX: What are the on-camera lights? Is there a certain one that you find works well in this application?

I can’t tell you exactly what they are, but we bought them on the net. They’re an off-the-shelf box that does warm and cool and comes with its own white plastic diffuser. They’re very small and very light. They get their power from the camera. The ones I used in Dorian I used much more sparingly, I think it was only three times in the show, and they were slightly less powerful. We went up a size for Jekyll, knowing how much more work they were going to need to do.

CX: With this style now known as ‘cine theatre’ and Dorian going overseas, do you think Kip will produce a series of works using these techniques?

Jekyll is inevitably being compared and contrasted with Dorian. I think there’s a danger that people assume because it uses the same form, they expect the same kind of experience. We are using the same form to tell very, very different stories. I think people are surprised that Jekyll was so serious.

I suspect that most of the world, like me, had never read the book. Although I read a lot of Robert Louis Stevenson when I was young, for some reason, I’d never read Jekyll and Hyde. I completely underestimated the seriousness of the work. It’s an exploration of the darker side of human nature. It’s not light and it’s not amusing in the way that moments of Dorian can be. Dorian is of course also a very serious story; I’m not saying it’s a knees-up comedy by any means, but Dorian allows more levity than Jekyll and Hyde does. That allowance is doubled because you’re being told the entire story by one person, rather than being shared between two. I think people have been surprised that we are doing a completely different work. It’s a completely different experience in the theatre, rather than looking only at the form and expecting a unity of experience.

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.