THE GAFFA TAPES

26 Feb 2024

A Day in the Life of a Record Producer – THE ANALOGUE TAPES

Subscribe to CX E-News

Snippets from the archives of a bygone era

Usually, ‘A Day in the Life’ narratives are a snapshot of a single day in someone’s enduring profession. However, my stint as a record producer only lasted for one day. It was way back in the analogue world of 1985, when I inadvertently became the record producer of my own songs after booking the leading recording studio in Manila and omitting to engage a producer.

The costly recording session was financed by the nightclub owner where Magenta, one of the bands I managed, regularly performed. We registered the record label CPR, a tongue-in- cheek reference to the first aid technique, but which represented the initials of our surnames; Coleman Posar Records.

The songs were ultimately pressed onto a 45 rpm single vinyl record, which then bore the inscription ‘produced from a digital master’. Annoyingly, it was a bad pressing that played out of time, and that digital tag probably accounts for why I’ve long been sceptical about CDs and vinyl records vying for audio supremacy as they face off in the aisles of record stores. Not only are they both spent technologies, but vinyl has been digitally mastered since the beginning of the 80s. So the whole debate becomes inconsequential.

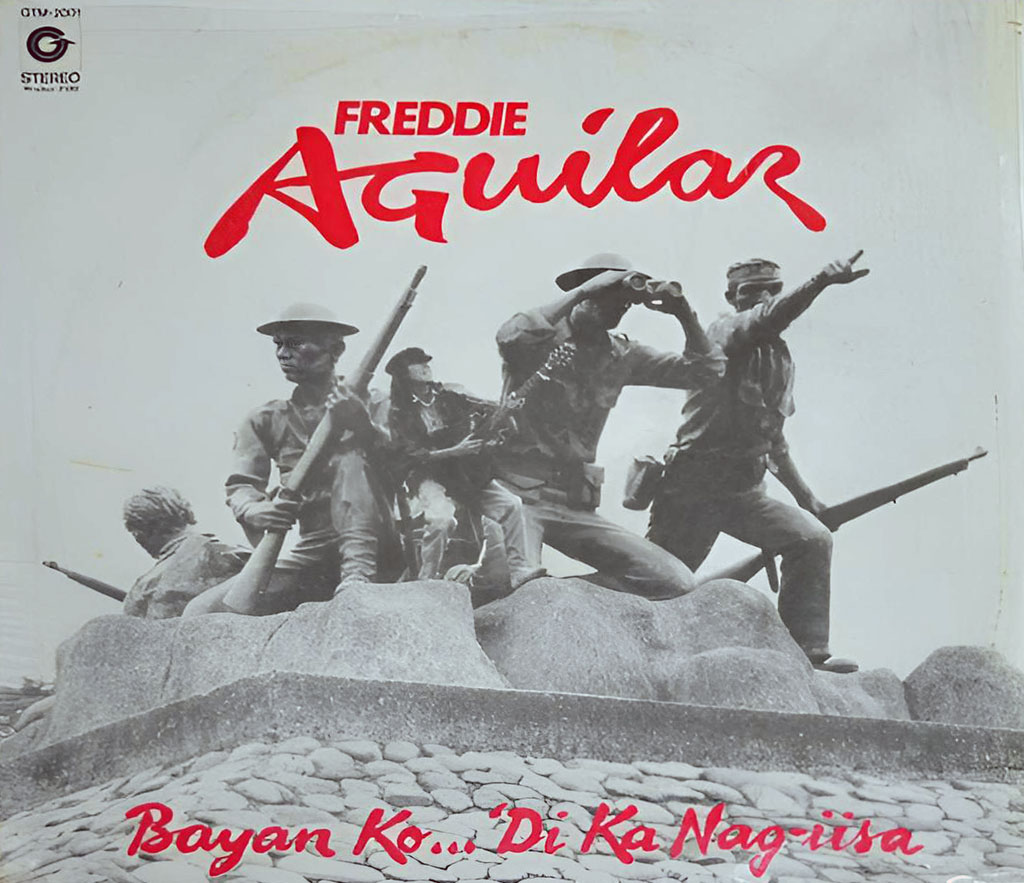

To arrange the recording session, I drove from my northern residence down to Manila to meet with Jose Mari Gonzales at his Cinema- Audio Studios. Jose Mari had been a box office matinee idol in the 50s and 60s. Cinema-Audio recorded the finest Filipino artists in the country, including Freddie Aguilar, whose song ‘Anak’ (young son or daughter) still remains the best-selling Filipino record of all time with over 33 million copies sold worldwide.

Jose Mari invited me to lunch at his residence with his wife and Freddie Aguilar. The lunchtime conversation centred around Freddie’s new album cover and the album’s anti-Marcos songs. Jose Mari stated that he had been personally warned by Marcos’ Commander of Presidential Security, Command, General Fabian Ver, about releasing the album, but he refused to be intimidated.

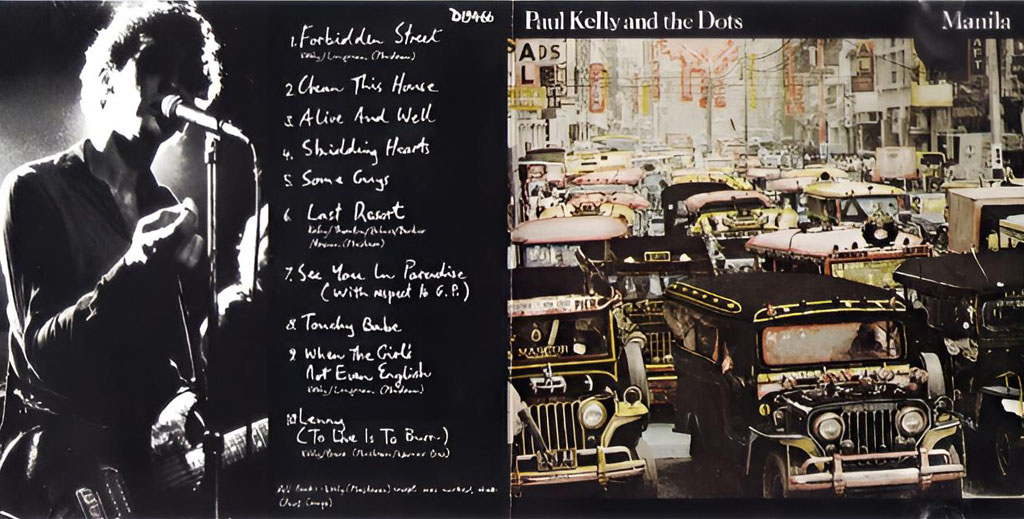

Another topic of conversation was an album recorded at Cinema-Audio by Australia’s Paul Kelly and the Dots some four years earlier, in 1981, entitled Manila. The album was released in August 1982 by Mushroom Records (re-released in 1990) and was produced by Paul Kelly and Chris Thompson. This was the last album by Paul Kelly and the Dots before he reformed under the Paul Kelly Band.

On the studio booking date, I drove the band down to Manila in a rented van. After helping set up in the studio, I entered the isolation booth to observe the audio engineer. It was then that I heard the soul-draining words, “So what do you want?” I had only recorded demos in minor recording studios around Sydney, and these were always one-man operations, from production to engineering to mixing. Here, I had a sound technician staring me in the face, who, like me, had no experience in producing a record. I’d been mixing this band nightly for over six months, but getting that mix down onto two-inch analogue tape in a studio was going to be a daunting task.

I decided to ask the drummer to put the basic drum track down and later do some fills. But he wasn’t comfortable playing without the accompaniment of the band. So after several takes and a few head shakes from the sound engineer, we had to abandon that idea. After lots of experimentation, we virtually did a live mix with the drums, keyboards, bass, and rhythm guitar, with the two lead female singers doing scratch tracks in an isolated booth. I was very fortunate to have two of the best female vocalists in the country, so when it came to putting the vocals into the mix, the girls did it in one or two takes, and that included doing the harmonies in real time. Then we did overdubs with the keyboards and lead guitar. We then mixed the 16 tracks in the same studio before leaving.

I was a bit green in 1985 about anything digital, but I’m guessing that either the studio or a third party dumped the mix down onto a hard drive to send to the pressing company. That’s how it would have gained its ‘digital master’ tag. I know there was no digital remixing as is done these days. To me, the analogue, digital thing is a mixed bag because major studios like Abbey Road still use SSL (Solid State Logic) analogue mixers in their main studios, and this is the same the world over. Some SSLs have built-in DAW control and automation, and SSL’s new Origin is a pure analogue console that fits into today’s hybrid workflow, where analogue mixers are married to digital workstations.

In a 2011 interview with Mark Lizotte (Diesel), I asked him about analogue and digital recording.

“It’s funny, you know, our first record in Memphis (Johnny Diesel & the Injectors, August 1988) was done on a Trident, which is a big, beautiful English board. But that went onto a Mitsubishi 32 track digital machine, 16 bit. When I ended up finishing the record with Don Gehman, we transferred it over to the analogue tape. Was there a big difference?

I don’t remember going, ‘Oh, that’s better now!’ When I listen to that record, it’s a great sounding record, but it’s not like I can go, ‘Oh listen to that analogue tape!’ I just think that we’ve got to stop blaming our tools. You know, digital stuff sounded pretty good 20 years ago, so what’s the problem now?” he said.

And in a 2012 interview with Ross Wilson (Daddy Cool, Mondo Rock), I asked him what his role as the producer of Skyhooks was, and he basically said he was a good listener. “I’m not a knob twiddler. For instance, with Skyhooks, which was the first big production job I’d ever had, I was more of an interpreter, and he (the sound engineer) would go and do the work. We got into this roll where I’d just say something and we’d discuss it, and he’d go bang, bang, bang, rather than me leaning over the desk and twiddling things and wasting time,” said Wilson.

Something that haunts me to this day is the fact that I played Jose Mari Gonzales a demo tape of other material I had written for Magenta, and he offered to manage the band. He had the number one studio in Manila and enormous contacts in the music and recording industries. This could have rocketed the band to national stardom and even launched my songwriting career. But, alas, for fear of losing control of the band, I declined. Sometime after the 1986 revolution, which deposed the Marcos regime, President Corazon Aquino appointed Jose Mari Gonzales director of the Bureau of Broadcast Services.

Cinema-Audio studio owner

When we eventually got the vinyl pressings, I rang a number of Manila radio stations to try to get some airplay. Here, there were no surreptitious backdoor payola deals; it was all done up front, even over the phone. The radio stations would tell you their schedule of payola fees to get your record played. It was all too dodgy, so we sold the singles from a merchandising table in the club where the band played. Up until the end of 1986, when I left the club, we had only sold a total of 37 copies.

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.