LISTEN HERE

10 Dec 2024

SEPARATION? I Thought We Were Mixing?

Subscribe to CX E-News

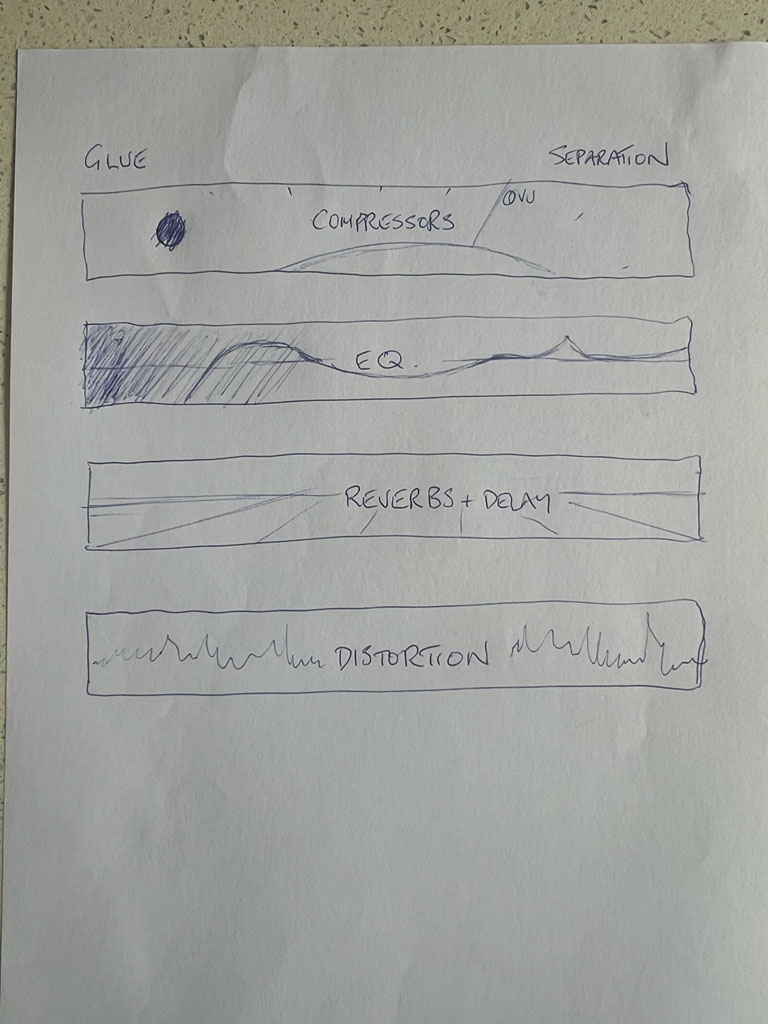

Sometimes, all mix engineers want to talk about is their preferred method for ‘gluing a mix together’. The rest of the time they’re banging on about separation. So, which is it? Are we trying to glue things together or keep them apart?

When people talk about mixing audio, they often don’t see the contradiction in their language, and there’s none clearer in audio than the divergent philosophies of mix ‘separation’ and the other involving adhesives and ‘glue’. For less experienced engineers these two concepts seem confusing at best, particularly in combination, where the two must seem like a recipe for disaster.

Now I realise it’s simplistic and glib of me to infer that mix engineers are in one of only two camps, and that these opposing sides are at loggerheads about how a mix should work. In truth, almost no-one in the business of mixing audio focuses solely on gluing things together, or conversely, keeping them separated. The true art of mixing involves a delicate combination of the two.

But what are these terms ‘glue’ and ‘separation’ really about? What do they mean, which tools do engineers use to conjure them, and how are they used in practise? Let’s investigate.

Tools That Glue

Glue is the clichéd term that essentially refers to anything that helps bring a sound or mix together and holding it in place. For many, glue’s main dispenser is the humble compressor, which, like a squeezable sauce bottle, is used to lessen the dynamic range of a sound, adding a modified tone or increased harmonic distortion along the way. There’s no ‘glue’ button on a compressor of course, but given how often people talk about adding this mysterious adhesive to a mix via their favourite compressor/limiter, you’d be forgiven for thinking there was. Glue takes other forms too, of course, but the compressor is by far the most commonly cited.

By controlling dynamics, compressors will typically restrict the scope of a mix; restraining its wildest tendencies and (depending on the way a compressor’s controls are set) holding the most dynamic elements in check. When combined with the tendency of some stereo compressors to narrow the soundstage, modify a song’s tone and increase the harmonic distortion content, here compressors are said to be adding ‘glue to the mix’. Glue can also be applied to a single sound, or groups of sounds, to add more targeted adhesion. And to extend the metaphor, some sounds will respond better to one type of compression than another, in the same way that a certain material may require a specialised glue to hold itself together or stick it to something else.

There are other types of glue, too… not just ones that stick mixes together with compression.

Collectively, a second group of loose affiliates go under the banner ‘effects’. Things like delays and reverbs, modulators and so on are all capable of acting as ‘glue’ in the right context. A mix can be bound together with effects by, for example, providing its elements with a common soundstage, so the various mix ingredients feel like they’re inhabiting the one space. Giving sounds a context in this way is one of the best methods of bringing (or gluing) a mix together. Delays and reverbs tend to pull on sounds in a mix, drawing them back into their surroundings rather than pushing them back as a compressor tends to do. Spatial effects like these also play on a listener’s sub-conscious, creating the illusion of a space that the person may already recognise, meaning that the listener’s own imagination is adding additional glue to the mix that isn’t there – an esoteric notion perhaps, but true nonetheless.

Whichever way you see or hear it, effects can have an adhesive quality, bringing sounds together. Things like flangers and phasers do the same – encouraging sounds to feel like they share a common world, weird though it may seem. Distortion and saturation effects might restrict the tone and shape of certain sounds too, by gluing them together either powerfully or subtly with a shared sonic fingerprint, making them sound more aggressive, mangled or blurry – together. Modern effects plugins like resonant frequency suppressors (very narrow multi-band dynamic EQs) can also be very effective at providing ‘glue’ to whole mixes or individual sounds.

Even panning can be considered a form of glue, by facilitating the placement of sounds in a mix so that they seem balanced and coherent. When a sound is panned too hard to one side, for instance, it may feel like it’s stuck to the wall of your soundstage, rather than inhabiting the space within it, and a pan pot can pull a sound back into the mix, thus making it feel more glued to the track.

I could go on with examples like this all day…

Separators?

But as you may have already opined yourself by now, some of the tools we use to glue a mix together can also be used to separate sounds from one another in a mix. Things like compressors, reverbs, delays, panning and distortion can all aid in the separation of sounds from one another every bit as effectively as they add glue to your mix.

So, what gives here? I thought we were trying to establish two lists: glues and separators?

No.

This conversation is not about two distinct sets of audio tools at all, but rather one.

Audio tools such as compressors, EQs, reverbs and so on are all on a spectrum of control, where every tool at a mix engineer’s disposal can be either a separator or a gluing agent, depending on what’s required by the mix. It’s simplistic – indeed wrong – to consider any of these tools as being well suited to only one role. EQs do not just carve out space in your mix, and compressors don’t just add glue. They are all capable of drawing sounds together or pulling them apart, depending on your mix’s many requirements.

The tool most commonly attributed by our audio community to separation control in a mix is, of course, equalisation. EQs are famous for being able to ‘carve out space’ thus creating separation between sounds and instruments. So, for instance an electric guitar might be ‘separated’ from a bass guitar in your mix by adding some midrange to its tone and filtering out the low end with a high-pass filter, thus avoiding the ‘space’ dominated by the bass.

But of course, some mixes start out with too much space to begin with – they don’t all start out life desperately in need of more. When you pull up a simple song arrangement and listen to it for the first time, you don’t scratch your head and think: “Oh my god, how am I going to find space in the mix to fit all this in?” Usually, it’s quite the opposite. You’re often struck by how stark and two-dimensional the soundstage is.

An EQ in this situation can be deployed to balance out sounds so that they occupy more of the same tonal space as one another, not less. To use our guitar and bass example again: in a mix where sounds seem too disconnected from one another, here we could cut a bit of harsh midrange from our far-too-bright electric guitar and boost some lower-mids to give the guitar more weight, while to our far-too-dull bass we could add a bit of bite with some midrange EQ and even some harmonic distortion thrown across it into the bargain. By creating tonal overlaps with EQ, we’re bringing the sounds together, not pulling them further apart.

Similarly, our clichéd mix glue applicator – the compressor – could be used to push a vocal forward in a mix by giving it even less dynamic, thus allowing us to push it a little further forward in the mix, separating it out from a busy song arrangement. A boomy kick drum could likewise be given added separation in a mix by adding a compressor to the channel and slowing down its attack time, letting the click of the drum through before controlling the thump. The result is a clearer, more visibly defined (or separated) kick drum sound in a busy mix context.

Distortion too can go either way, acting as a gluing agent in one mix context, and a separator in another. You could, for instance, add distortion to that kick channel we just talked about to further enhance the bite of the drum’s impact. Sometimes, counter-intuitively, distortion on an instrument in a mix can enhance its clarity.

And of course, effects of all kinds can add definition, separation and specialised character to a sound in myriad ways, defining and separating sounds out from the crowd, even when the arrangement is sparse. To me, the appearance of a sonic void is a more attractive sounding thing than an actual void. ‘Air’, ‘plasma’, or ‘gravity’ – call it what you will – between the mix elements sounds far more euphonic to me than a hole.

The Spectrum

Mixing is all about context. Every mix is different, and as an engineer, it’s important to stay open to each one’s unique requirements, not approach the mix position loaded up with our own set of biases or ‘techniques’ for X, Y and Z. Some mixes start out life over-arranged and full to bursting with instruments and sounds. These may need you, the mix engineer, to lean your set of audio tools more towards the separation end of the spectrum. Other mixes may be stark, under-arranged and oddly misaligned in their tone. For these songs, your same tools may be deployed as gluing agents.

Never think of any of them as serving only one purpose.

And one last tip, the ultimate example of a tool that’s perfectly suited to either role – that’s the most overlooked tool in the kitbag in discussions like this: fader level control.

’til next time.

Andy Stewart owns and operates The Mill in the hills of Bass Coast Shire, Victoria. He’s happy to respond to any pleas for recording, mixing or mastering help… contact him at: andy@themill.net.au

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.