The Gaffa Tapes

18 Aug 2022

The Gaffa Tapes: Death of a Salesman

Subscribe to CX E-News

Snippets from the archives of a bygone era

A broken guitar string in 1971 prompted me to walk into the newly opened Wadsworth Stamford music store in Bankstown Square, Sydney, where by chance I gained my first sales position—that of musical instrument salesman.

These were notable times in the music industry: The Beatles had broken up the year before, Elton John had his first international hit with ‘Your Song’, and Paul McCartney had just formed his new band, Wings.

Sheet music, especially with guitar tabs, was a hot seller; and my first enterprise was to plaster the entire eastern wall of the store with sheet music, which ultimately paid the store rent. However, the real profits were in organ sales, which were booming at the time, but my three piano chords and one-finger melody neither impressed potential customers nor attracted any sales.

Wadsworth Stamford had the Wurlitzer organ distributorship and the store also sold the more affordable range of Lowrey organs. This was the era when Lowrey incorporated the ‘automatic rhythm’ box into its range—an array of annoying drum-like beats that I could never quite come to terms with. And I was horrified just a few years later in 1975 when I saw Paul McCartney incorporate a similar sounding rhythm machine in Wings’ performance of Bluebird at Sydney’s Hordern Pavilion.

“It’s amazing what they can do these days isn’t it?” McCartney told the audience.

Paradoxically, it was the ‘Silent Generation’—the generation before Baby Boomers—that no longer wanted to remain silent in the burgeoning electronic music world. So the Lowrey Genie organ with its ‘easy play’ one finger chords, auto bass, and rhythm machine became their instrument of choice.

Whilst I was selling acoustic guitars worth around two hundred dollars, Lowrey organs worth around two thousand dollars were gathering dust. So Frank Wadsworth arranged keyboard lessons for me. However, I still failed to impress, so he employed a keyboard player/salesman who was immediately promoted to Store Manager, and I was shipped out to another branch and assigned to more mundane duties. This ultimately brought about my demise.

Some seventeen years later, somewhat frustrated by the diminishing opportunities after years in the music industry, I re-entered the world of sales—this time as a broadcast sales representative. I was soon to learn the enormous difference between customers walking into your store, and you having to go out and find them.

The pro audio and video sales business has always been littered with personnel who would prefer a hands-on role in the industry rather than being summoned regularly to the Sales Manager’s office where admonishing fingers were pointed when sales were down. George Bernard Shaw’s crushing remark aimed at teachers from his 1903 play ‘Man and Superman’ was, “Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.” Similarly, a great contingent of those who couldn’t participate creatively in the audio/video or music industry ended up in sales.

My business card read ‘Sales Engineer’, which was a bit of a stretch for someone trying to flog Sonifex cartridge machines to radio stations. Carts still reigned supreme in an analogue tape-based world; they were used for radio commercials, jingles, station identifications, and music. But the digital world was closing in, and in late 1989 an ABC Radio team led by Spencer Lieng won approval to implement their new digital innovation. This was D-Cart, which was a digital audio editing, recording and playback system consisting of a keypad and software application that replaced the need for cartridge and reel-to-reel tape machines.

Paul Penton was one of the ABC Radio engineers that used the D-Cart system when it was introduced all those years ago. I contacted Penton, who still works for the ABC as Manager of Audio Radio Operations, to chat about D-Cart.

“Believe it or not, we still use it,” said Penton, who added that D-Cart was still in transitory use in some applications pending new solutions. He said that ABC Radio National went on to incorporate other digital solutions such as the Stagetec audio consoles with NETIA radio assist (pictured) as part of their ongoing digital solutions.

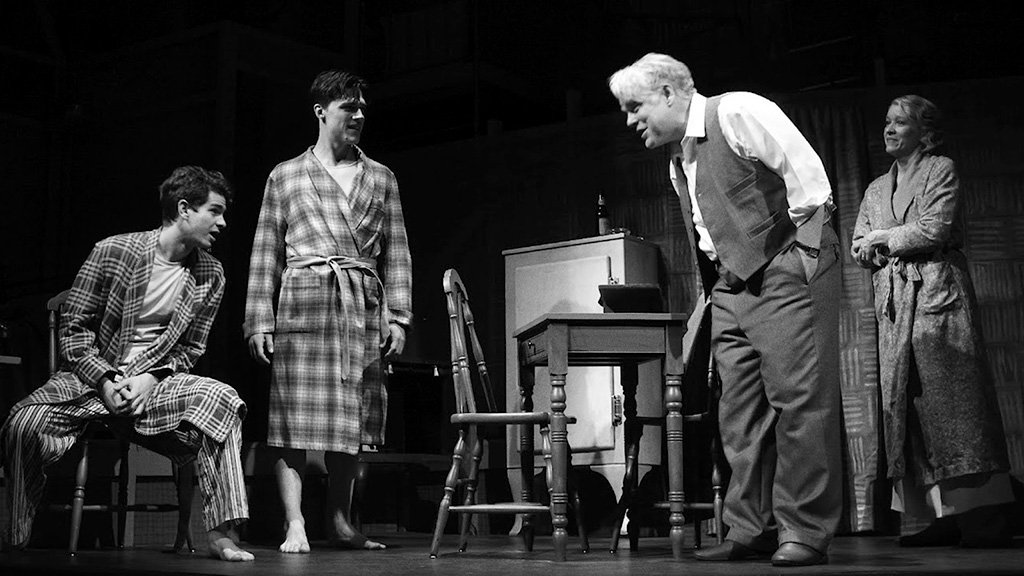

In Arthur Miller’s play, Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman burns out in his early 60s. He is deluded, out of touch with a changing world, and suffering from a loss of identity after a lifetime on the road in sales. Conversely, I was excited about a world that was rapidly turning digital, but I grew tired of the cold calling and the demanding sales targets, which constitute the millstone around every sales representative’s neck.

After a hiatus of some years I joined Audio Telex where I spent the next five years unsuccessfully trying to mould a sales position into a technical position. Despite some success in design and troubleshooting, management didn’t want me rubbing shoulders with them. “You’re just not the type,” I was told.

Management soon became aware of my displeasure of the daily grind on the road. Thus I was demoted to office duties with the loss of the company car; and I got the idea that they were not exactly thrilled to have me around.

The demotion was analogous to the tale of Brer Rabbit, who cried, “Whatever you do, don’t throw me into the briar patch.” But the ‘briar patch’, in the form of the office was exactly the escape I needed. Here, amongst other duties, I was kept busy intercepting calls from troubled installers who were mystified as to why their 100V line audio systems were blowing up (invariably due to installation faults). And I was sometimes dealing with installers whom I surmised thought Ohm’s Law was probably a 70s television police drama.

My new role was welcomed by the service department, which was often overloaded with calls from troubled installers that they didn’t want to deal with. The position also gave me the opportunity to work on a couple of designs with my good friend Rudi Smit who was Audio Telex’ long serving Design Engineer, and the unsung hero of the company who designed and manufactured the bulk of the company’s 100V line hardware and other equipment.

In an ironic twist, for my services, which included callouts on problematic installations, design, and liaising with the technical and service departments, I was promoted out of the briar patch back to Sales Representative. I was back on the road where I once again began to self-destruct, and subsequently Audio Telex and I parted company.

I don’t think I lasted more than a year in my final sales position at Greater Union, where I remember doing a lot of audio design trying to win tenders so as to keep the Sales Manager at bay. Tendering for projects is a lengthy process, which can take weeks. I was once called out to a major shopping centre under construction, given a hard hat, walked through the site with my plans and asked to qualify certain aspects of the design while the installation was in progress. The problem was we didn’t have the tender. Unbeknown to the installer, the project manager had given the tender and my plans to another company.

The second problem with the lengthy and time-consuming process of tendering was the ‘second quote’. This was often practiced in licensed clubs and other venues where a committee had asked for two or more quotes, irrespective of the fact that an installer had already been surreptitiously appointed. So, I would often be the dummy doing the dummy quote.

It was on a rainy Friday afternoon two weeks after handing in my resignation to the Sales Manager, and now devoid of my company car, that I watched the office slowly empty while I waited for a taxi that didn’t arrive. Thankfully, the General Manager of Greater Union noticed me alone in the office and drove me to a railway station. I never returned to sales.

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.