PEOPLE

5 Jun 2023

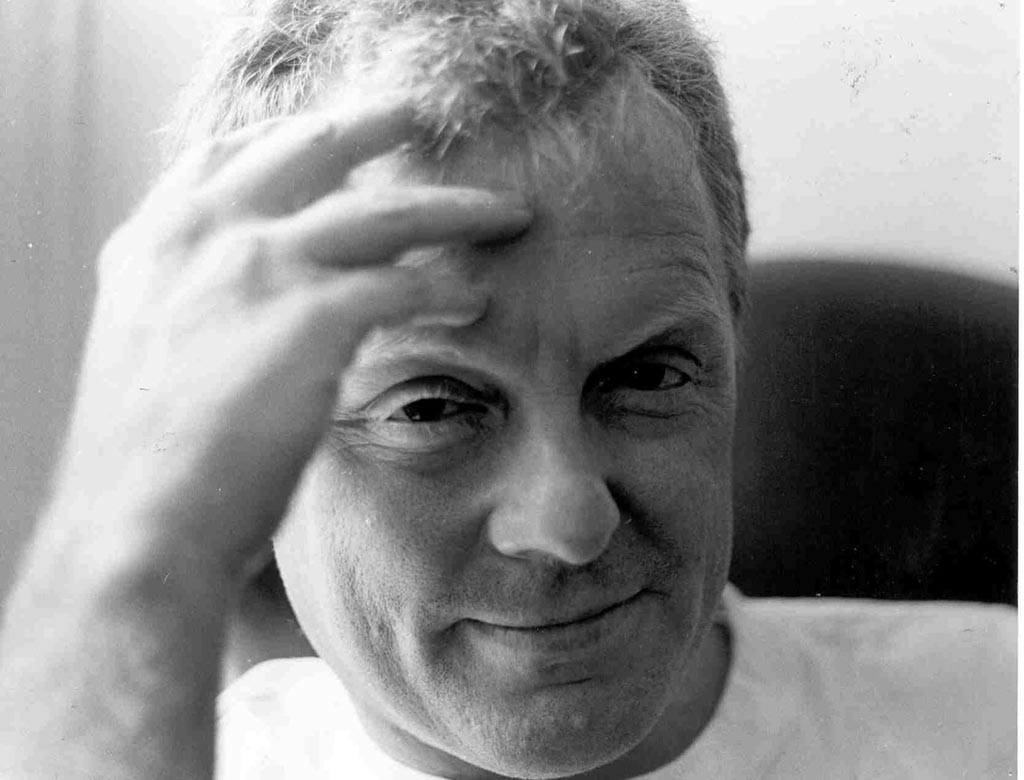

IN PROFILE: PAUL CHARLIER

Subscribe to CX E-News

Paul Charlier has composed and sound designed for approaching 200 productions across theatre, dance, physical theatre, film, TV, radio, and audio-visual installations. He started out with industrial noise outfits SoliPsiK and SPK and since then his works include: Liv Ullman’s A Street Car Named Desire, Stephen Soderberg’s Tot Mom, Judy Davis’ Faith Healer and Dance of Death, and a lot of plays with Neil Armfield at Belvoir in the day, Michael Blakemore’s Copenhagen at STC, plus his Deuce on Broadway and Afterlife at the National Theatre, London; Marrugeku’s Jurrungu Ngan-Ga (Straight Talk), DV8’s The Cost Of Living and Force Majeure’s Already Elsewhere. He scored the films Candy, Last Ride and The Final Quarter, and sound designed Looking for Alibrandi and Paul Kelly: Stories of Me.

I don’t get around to asking Paul Charlier if he has any formal education in sound design and music composition. It’s evident speaking to him that his expertise in the field has largely come from experience. “I’ve always had this thing that the way to learn is you find the person and just go talk to them,” says Paul. “It’s probably a pre-internet way of learning.”

In 1992 Paul self-designed a research trip that he was very grateful to get funding for; “I’d just seen Aliens, the 1986 sequel to Alien. It has an extraordinary mix in the way of integrating voice, music and sound effects. I just wanted to find the person who did it. So I went through the credits and started sending faxes saying I’d be in England, can I meet you?”

When Paul went to meet Graham Hartstone at Pinewood Studios, he was expecting “some young cowboy in his twenties who was pushing the limits.” What he found was a much older gentleman with a wealth of experience who explained to Paul how everything he learnt working on James Bond films and David Lean films had informed his work on Aliens. “At that point I realised it’s not a moment-to- moment thing, but a huge tome of experience that you gather and develop project-to-project.”

When Paul started working as a sound designer in theatres he was working on reel- to-reel tape. Over his career he has worked through the transition to CD and then to computers. Each medium has its limitations, but he explains the experience of “just hacking it through with whatever is available” has developed skills in being able to find his desired effect with whatever he has on hand.

“Stage managers in the 90s were operating lighting and sound off reel-to-reel and analogue mixers with no automation,” recalls Paul. “It was very hands on. The advantage of that system was that they were very responsive to each performance. They could automatically adjust if an actor was under-powered or something changed during a performance.

With all the great aspects of automation, it can be hard now for the operator to adapt within a live performance. The skill and knowledge with using QLab is knowing how to put the material together to allow for flexibility so there are ways to adapt depending on the performance.”

He uses an example of a recent score he designed for Griffin Theatre Company’s production of Suzie Miller’s Prima Facie. “The first cue is 16 stems that start together and then each of the following QLab cues remixes it. It’s very flexible with the performance. If lead actor Sheridan Harbridge’s timing changes, the mix changes with her. It’s not one pre-recorded piece that sits under the scene. Different instruments and parts come in at different times depending on the performance. It’s complicated, but it’s what I’ve learnt to do from working in different formats.”

Paul worked with physical theatre company Stalker in the 90s, which he describes as; “a master class in learning how to write music that could follow the action.” When performing high-risk work, such as jumping off sets on bungee cords, the performer won’t jump on the fourth beat of the bar, but only when it’s safe. “That was in the CD era. One version of Stalker’s Blood Vessel was on five CD players, to break the music up across different discs and keep it in time and in line with the performance.”

Another major factor in designing sound is not just how it integrates with the performance, but with the audience. “One of the things I always hated was front of house stereo that was way up above the audience,” admits Paul. “I found it very disorientating because the sound was coming from the gods and the story was happening much lower on stage.”

With each show Paul will enter the theatre and see what the venue has and how he can reconfigure it to get the best effect for that specific space; tech specs can’t always be relied upon to be up to date. A trick he often uses is turning speakers around and facing them at a wall or the roof, so the sound bounces off. It creates a more natural diffusion and means the sound coming from the speakers is merged with the actors’ voices.

“There’s a trend at the moment where most of the new sound systems are set in what’s thought to be the best position for radio mics and everything else revolves around that,” reports Paul. “Over the last couple of years, I’ve started to ignore the house systems.

What I’ve been tending to do is use a pattern of three Meyer Sound UPJs or UPAs, or larger depending what the theatre has, plus a Meyer Sound sub and putting them either behind the set or back just above the set or sometimes within the set to pull the sound down. With Prima Facie, the speakers are quiet low on the set because we wanted the music to come from the same place as the actor’s voice.”

In addition to integrating the sound with the action on stage, this system has advantages when designing shows that will go on tour. “I started trying to attach the speakers to sets in a way that the sound system toured with the set, so we weren’t dependent on different set ups in different venues. Sometimes you will use the existing house system to elaborate it or fill in the gaps depending on the layout of the theatre.”

But, of course, the design still has to allow for flexibility when touring. “Worst case scenario, you just have to do a stereo show that can slot into every venue. For Prima Facie, there are two versions in QLab side-by-side. There’s the multichannel surround version plus a stereo mixdown within QLab. So if the venue is smaller and limited, they can play the stereo one. If they have stereo and subs, they can play stereo and the sub channel.”

While there are challenges to adapting to different venues, Paul appreciates that theatre allows him to invent playback systems to be unique for each space and each show. This attention to how the audience will hear the performance is perhaps due to Paul’s belief in the pleasure of sound and of listening. And this belief extends from the listener experience to sound’s role in narrative. “There’s a pleasure in the colour of music and sound. When it gets too literal or treats the audience like they’re idiots, I get bothered by that. If the actors are portraying the story perfectly clearly, why do you need to double-up on that?”

“Prima Facie starts with ‘user friendly’ techno music that breaks apart under the performer, it doesn’t necessarily underscore her feelings, it gives the actress something to play off.

Sheridan is doing an extraordinary job of the development and disintegration of the character after a rape, so the music doesn’t need to reiterate that. Rather it is meant to be about how alienating and unforgiving the environments she finds herself in – the police station, the hospital, the courtroom – are.”

He describes this desire not to overscore narrative as; “pushing against the waves at the moment. We’re back into a way of scoring in theatre, film and TV where things are over- emphasised, and there’s a lot of this is what this scene is about in the music. Mostly I think it comes from a fear of silence, that silence means nothing is happening, or a lack of confidence that a scene is working, or a fear that the audience isn’t paying attention. I don’t know; maybe they aren’t. It’s being talked about in a different light in terms of mixes for programs on streaming services, where they’re very aware that half the audience isn’t looking at the screen all the time, but looking at their phone, and only listening to the program. So there’s a whole new type of sound use that is developing that is designed to trigger you to look up from Twitter and look at the screen because if you don’t you’re going to miss an important visual plot point.”

While most people would most likely guiltily admit to what Paul is describing, he maintains that split focus is not knew. He worked on the sound design for the 2000 film Looking For Alibrandi. Wanting to know how younger audiences were responding, he went on a Saturday night screening in the western suburbs of Sydney. Despite that there weren’t smart phones in a cinema at that time, he describes groups of teenagers having picnics on the floor below the screen and talking all the way through the film. “Split focus was always a part of it. The phones aren’t the culprit, they’ve slotted into existing habits.”

The tome of experience that Paul has developed over his career is incredibly broad. From sound effects to music composition and acoustics, but he maintains that it’s the integration of all those elements that makes a sound design. “There’s no division”.

Prima Facie Photos by Brett Boardman

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.