LIVE

11 Mar 2025

KAGAMI

Subscribe to CX E-News

Ryuichi Sakamoto and Tin Drum’s Groundbreaking Mixed Reality Concert

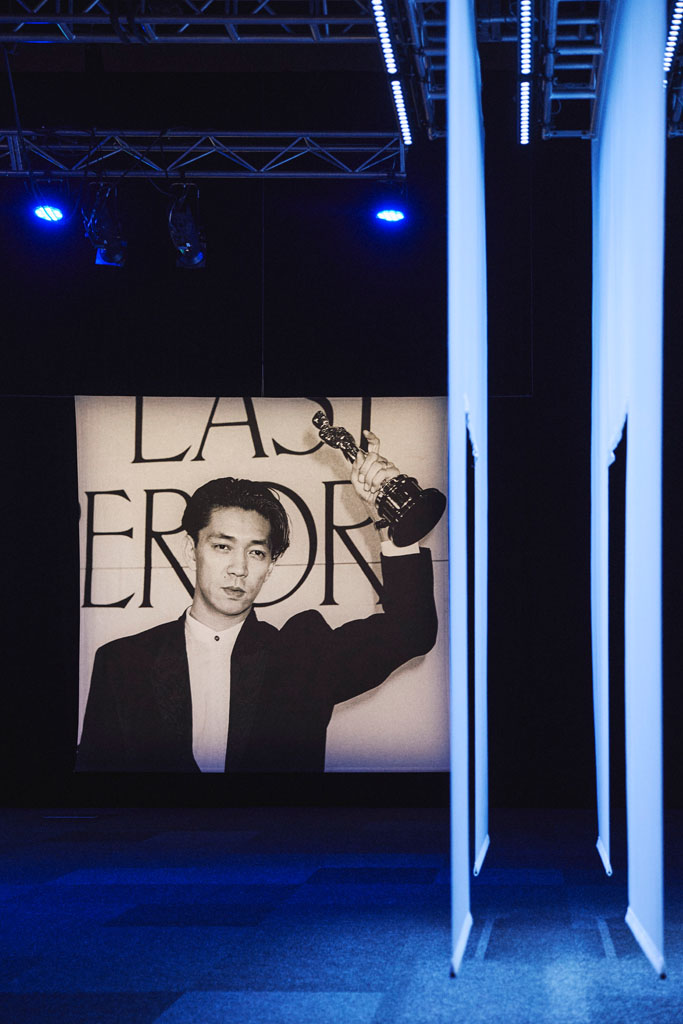

Even if you’re not familiar with Ryuichi Sakamoto, it’s likely you’ve heard his music. Launching his career as part of electronic music pioneers Yellow Magic Orchestra, he went on to release a series of influential solo albums, composed music for the opening ceremony of the 1992 Olympic Games, and won an Oscar for his score to the 1987 film The Last Emperor. He even acted alongside David Bowie in the 1983 film Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, for which he also composed the score, whose main theme, Forbidden Colours, became a hit. Constantly experimenting, Sakamoto produced multimedia works, collaborated across disciplines and genres, and was awarded one of the world’s highest cultural honours, the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, in 2013.

On Wednesday 19 February, I went to the media preview for the extraordinary Kagami, a mixed reality piano recital performed by Sakamoto, now almost two years after his death. Despite having two cameras with me and having totally free reign to photograph it, I can’t show you a single image of the show. Not because of bad light or my shonky photography skills, but because the visual part of the performance takes place in a pair of mixed reality glasses that defy photographic capture. Sure, I can show you what the infrastructure in the room looked like, but in describing the truly novel and breathtaking visuals, I’m left with just words.

Kagami (mirror, in Japanese) was created by Sakamoto and long-time friend Todd Eckert (as director) and Todd’s company Tin Drum.

It is a 50-minute-long piano recital consisting of 10 pieces, played by Sakamoto on grand piano. Apart from the solo piano, Sakamoto speaks briefly three times, introducing pieces. It is very Japanese in spirit; restrained, zen-like, and beautiful.

The audience enters the space, in this instance, a blacked-off exhibition hall in the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre. A circle of chairs rings the room. You take your seat, and staff hand you your glasses and the computing ‘puck’, or ‘pack’ that runs them. They ask you to put on the glasses and confirm you can see a red cube rotating in the centre of the room. I can. That’s means the device is booted and running.

A circular truss hangs above the centre of the room. It’s rigged with six d&b audiotechnik loudspeakers spaced around its perimeter, and one in the centre pointing straight down.

Two d&b audiotechnik subs are flown next to them. There are also some simple LED fixtures around the truss. Another truss circles the room, which must have been 30 metres in diameter. It has regularly spaced LED Pars, LED pinspots, a few movers, and some smaller LED fixtures I can’t place. On the floor under the centre truss, white tape marks out a square mandala about four metres wide.

In silence, the room goes dark, and Ryuichi Sakamoto appears sitting at a grand piano in the centre of the room. It is life size. He begins playing. The piano sound, coming from the d&b PA, is as close to sounding like there is really a piano in the room as I have ever heard. Both Sakamoto and the piano are not made of real video – they are rendered as very high-quality graphics. They are completely three dimensional.

During the first piece, a low fog starts floating to the centre of the room from all 360 degrees, starting about 20 metres out. It’s not real. People get out of their seats and follow it, as do I. That’s when the magic really starts. You realise that as you get closer to the maestro, he becomes more realistic and in focus. You can walk around him (they encourage you not to go inside the area marked by white tape). I stood over his shoulder and watched his hands playing the piano, and it looked real. Amazingly, I walk around the piano, which has its lid off. The sound exactly follows what would happen sonically if you walked around a real piano.

I am very, very impressed. Particles float through the air. At the end of the piece, the video fades.

When it fades up again, you start to see what this technology is really capable of. In response to an angular, rhythmic piece, beams of red and white laser-like light start forming a structure in the air that you perceive as being 40 meters across and two storeys tall. They grow and reproduce according to the structure of the piece, like a three-dimensional painting by Mondrian. From here, the graphics become more amazing with each piece.

From then, I see visual effects I have never even considered as being possible. In one piece, a roughly 3 x 3 metre ‘window’ opens behind Sakamoto, about six meters in the air. It is angled down at roughly 30 degrees.

Within this window, a real video of a progress through a snowy forest plays. It’s exaggerated light beams from the window onto Sakamoto’s back and around him. It looks transcendentally beautiful.

In another piece, two concentric circles grow out of the floor, roughly 12 and 15 meters away from the centre. At first, they are rings of light, but then they grow into two-storey-tall still images of Tokyo that bend around 90 degrees of the circle. The are two rings of three images, with gaps between each image. Both rings rotate. I walked between them as they rotated. They are somewhat transparent, and you can still see Sakamoto. I found myself putting my hand into them with childlike wonder.

Then, Kagami takes the floor out from under you. A tree grows out of the piano, and its roots extend into the ground. The floor has gone black, and you are seeing tree roots grow in a complex tangle over 20 metres in diameter under you, going down 10 to 15 metres. Your brain is now convinced you are hovering in air.

This effect is taken to its absolute extreme when you are hovering above Earth itself and the entire performance space is the vastness of our universe. Some people are going to have pretty extreme reactions to this. Our audience broke into spontaneous applause, which is always a bit odd when you know you’re applauding playback.

As acknowledged by the pre-show announcement, this tech isn’t perfect. The glasses use some kind of polarisation, which makes your fellow audience members all but disappear, but which the brain interprets as ‘odd’. About a third of my field of vision was blurry, and you have no peripheral vision to speak of. There’s always a slight lack of substance to any digital visual. All that being said, the experience is still incredible, and it’s startling to think what this technology is going to be capable of in the near future.

Behind the Mirror

After this extraordinary experience, I was lucky to sit down with Director, Producer and Art Director Todd Eckert of New York’s Tin Drum. Tin Drum is a global collective of artists, technologists, designers and scientists founded by Todd to create works in mixed reality. Todd himself started his career in music journalism at the tender age of 14, worked in the arts and film, and was recently the Director of Content Development for mixed reality device manufacturer Magic Leap, which led him to found Tin Drum in 2016.

I had a million questions, and started by asking what gear was involved in what I just witnessed. “The mixed reality glasses and the computing pack you were wearing were made by Magic Leap,” confirms Todd. “We don’t have to specify lights as they’re pretty generic wherever we go. The sound system is d&b audiotechnik, running Soundscape. Everything else we created. The actual video delivery mechanism is gaming engine Unity. The capture process was done by a company called 4DViews who are based in Grenoble, France. We did the capture and recording at Crescent Studios in Tokyo using 48 cameras and a lot of close mic’ing of the piano. We had to reprocess, refine, and change absolutely every facet of the raw data that we created.”

I haven’t had much experience with augmented or mixed reality experiences like this, and I have no idea where the content is actually coming from. Is it streaming? “No, all of the content is stored individually on each computing pack, and all of the packs are locked together with timecode, as is the lighting and audio,” explains Todd. “We had to create a bespoke piece of software to do that.”

The positional data that changes your perspective on the content as you move around the room is also running in the computing packs. “The computing pack orients itself when we first initialize the device. Unless something goes wrong, your position isn’t being updated by anything external to the pack.” I ask about the 12 or so 20 x 20cm QR codes hung around the perimeter of the room – do they have anything to do with the positioning? “Yes,” Todd continues. “The devices are state-of-the-art, but sometimes they’re like precocious children and need to be affirmed. Finding the floor, for example, is, predictable, but it was very important to all of us that if there was any potential for drift or the images coming off-centre, that we’d be able to fix it very rapidly, and so we put those QR codes there. But it also orients Ryuichi so that the audience gets the best vision of him. It’s there if we need it, but we’re not constantly looking for it, because that would burn through our computing power.”

Todd worked on the show with Sakamoto and the technical team over many years; “The art design was all mine, and every single song has a reason why it is what it is,” states Todd. “The process of creating visuals was to distance the show from feeling like a recital.

It was very important to me that this not only appealed to people who already loved Ryuichi, but could also entice and excite an audience who were unfamiliar. It is more fulfilling than just a person playing piano, and we are able to express different ideas with each song. The first song, with the fog coming out, is designed to encourage the audience to move towards him. The next song, ‘Aoneko no Torso’, has an incredibly fluid melody, and I pulled the particles that float around Sakamoto out of video of the sun glinting off of the sea in Thailand.”

The astonishingly perfect piano recording and playback is courtesy of Audio Designer Kazuyuki ‘zAK’ Matsumura, who captured the piano with extremely close mic’ing so as not to get in the way of the cameras. A d&b Soundscape immersive audio processor takes the multitrack playback and positions it perfectly in the d&b PA cluster, ensuring the as-close-as- possible-to-real result.

I asked if there was anything going on technically that I wouldn’t be able to pick up on. “You know how the show goes into complete darkness a couple of times?” asks Todd. “Given that the mixed reality devices require the recognition of the floor to remain positioned virtually where they are, we needed a way to give them that information in a way that you can’t see. We actually flood the entire area with a very specific frequency of infrared, from specialised fixtures we tour with.”

Aside from the special IR fixtures, the show tours with fairly minimal tech infrastructure. “We’ve got a few racks, but not a crazy amount,” relates Todd. “We don’t tour lights; we pick them up regionally. Same with PA – we can always get what we need in terms of d&b. We’ve got an anchor team of five people, including a stage manager. It’s not a massive group, and I’m really, really lucky in that I have an astonishing crew that just figure it out wherever we are. And by the way, the crew here in Melbourne has been crazy good! I guess it’s the same as any touring show, really. Every space is unpredictable. How the devices work can be impacted by magnetic charges that you can’t see. Power grids are all different, so you have to accommodate that.”

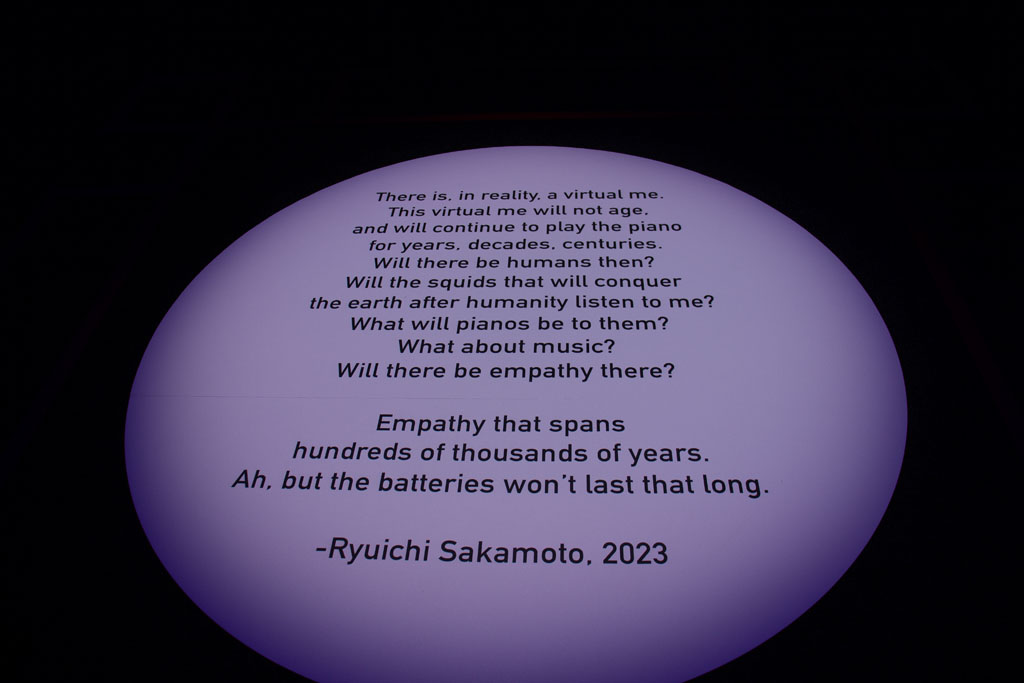

Despite all the technology deployed on Kagami, the show feels deeply organic, and an extremely human meditation on death. Sakamoto himself went into hospital halfway through production and didn’t come out for a year. He died not long after the project was completed. A projection on the floor in the antechamber before you enter the space are Sakamoto’s typically playful musings on his eternal digital life.

From the editor: “The producers have only released this one simple render from the graphics engine running the show. While that’s frustrating for me as a magazine editor, I am totally behind this artistic decision. Kagami needs to be experienced. Even with years of covering tech and theatre, I was left awestruck by the piece.”

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.