Lighting

9 Nov 2022

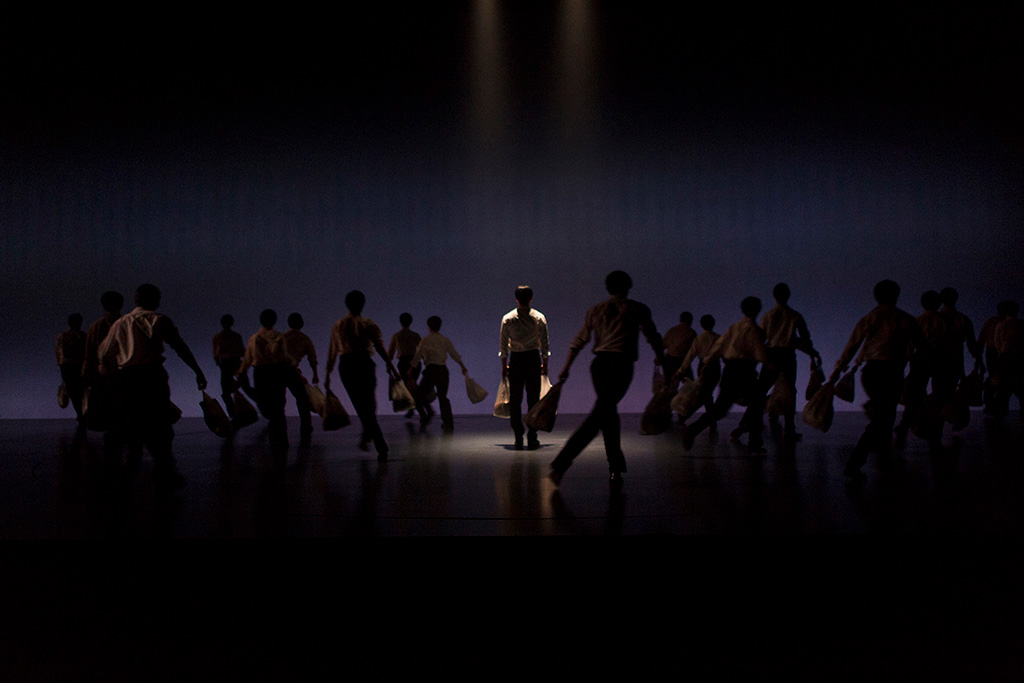

Nick Schlieper celebrates 100 shows as LD with Sydney Theatre Company

Subscribe to CX E-News

Nick Schlieper is one of Australia’s most highly awarded designers, having received six Melbourne Green Room Awards, six Sydney Theatre Awards (two for set design and four for lighting design), the inaugural 2013 Australian Production Designers Guild Best Lighting Design Award, as well as five Helpmann Awards.

This year alone, Nick has lit Bangarra Dance Theatre’s Wudjang: not the past, Opening Night for Belvoir Street, North by Northwest (Kay and McLean Productions), and Phantom of the Opera (Handa Opera on Sydney Harbour). As covered in this magazine in the August 2022 edition, he lit Sydney Theatre Company’s game-changing The Picture of Doran Gray, and then followed up with another Kip Williams’ “cine-theatre” tour de-force, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which we cover in the coming pages. It’s this production that marked an astonishing 100 productions that Nick has lit for STC.

Not slowing for a second, Nick is already working on his 101st production for the STC, Shakespeare’s The Tempest starring Richard Roxburgh, before heading to Munich to light Penderecki’s opera Die Teufel von Loudun. Somehow amid this schedule, I managed to interview Nick about his career, and the remarkable feat of lighting 100 productions for Australia’s premiere theatre company.

CX: What was the first show you lit for the STC, Nick, and how did you come to work for them?

It was Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler at The Wharf, with the most electrifying performance by Judy Davis. It turned out to be a very auspicious debut. There were people scalping tickets on the front steps for up to $80 or $90 in 1986, and tickets were much cheaper in those days. It was a sensational performance. It was a great fluke to land that as my first show there.

I started off my career not sure if I wanted to be a lighting designer or a set designer. I fell into a job at The Independent in North Sydney, near the end of its days, and decided not to go to Sydney Uni to do arts/law, which is where I was headed. After that I worked a number of jobs. I did a six-month course with English lighting designer David Reid, who The Australia Council had brought out. That course was administered by The Old Tote, the forerunner of the Sydney Theatre Company. While I was there, they offered me a job as an ASM. By this stage I had delusions of grandeur and had decided I wanted to really be a director. In those days that’s how you learned to be a director; you were a stage manager and became the director’s right hand. That caused a four or five year long career diversion.

I promptly closed The Old Tote. Before I’d hit 21, I’d closed two theatre companies! I ended up with a job at Opera Australia where I called half the repertoire as a stage manager. For three years, I was just calling shows. I then thought, hang on, this was not really what I wanted to be at all. I moved back into lighting design. That was tough for a couple of years. Freelance lighting designers were still fairly rare, and there were maybe only four or five around by then. It was the very early 80s and it was certainly tough to make a living. I think it’s safe to say publicly that Richard Wherret, Sydney Theatre Company’s first artistic director, blackmailed me into getting them out of a jam.

He asked me to stage manage a tour of STC’s very large production of Nicholas Nickleby with a half-new cast, going to Melbourne and Adelaide. It had been a massive success in Sydney, but they were in a jam. I think getting to light a fantastic show as my first show at Sydney Theatre Company was the quid pro quo for me taking on the gig. That was my swan song as a stage manager. After that, I started lighting roughly two shows a year at STC.

CX: Out of the next 99 shows, which ones still stand out for you?

That’s hard, but going back through a list has stirred a few memories. It’s hard to look past the most recent past, and The Picture of Dorian Gray. There was 2018’s Harp in the South, if only because of the massive size of the undertaking. A production I think never got the attention it deserved was 2017’s Chimerica. I’m also quite proud of Endgame in 2015 with Hugo Weaving as Hamm, and Waiting For Godot with Hugo Weaving and Richard Roxborough in 2013.

Then there’s ‘The Cate Blanchett Years’, because we did so many shows with Cate; Uncle Vanya, Big And Little, War Of The Roses, and A Streetcar Named Desire. There was also a much lower profile show, a double bill that Cate Blanchett and Andrew Upton directed one half of each, called Reunion and A Kind of Alaska at The Wharf, where we filled the entirety of Wharf One with several inches of water!

It’s funny, because the great big shows like War Of The Roses are the ones that you expect people to remember, and rightly so, but there are all these other, much smaller scale shows that I often remember just as fondly. It’s interesting the way the smaller shows rear up in my memory and I think ‘yes, that was a really good piece of work.’

CX: Would you say there is a unifying approach or philosophy that you bring to every single show, or do you adapt and change your intention according to the work? Do you feel that there’s a common thread through your work?

I think my aesthetic is consistent. I don’t think anyone can do anything about that; we all have our tastes. That said, given that vast variety of pictures that go through my mind when I look back, it’s obviously always in the frame of whatever production it is, but aesthetically I imagine that there is a fairly identifiable through-line there.

Philosophically, I know I haven’t changed. I’m stubbornly consistent on that score. I think if you do not work on a show right from the get- go and genuinely have an input into shaping what it ends up both looking like and being like, I think you’re not doing the job. I certainly have stubbornly continued to do that for a very long time.

CX: If you were forced to, how would you describe your aesthetic?

The cliche that always pops up in reviews is “painterly”. I guess there is some truth to that. It is an awful cliche, “painting with light”, but my brother was a painter, and I learnt a great deal about what I do from watching his pictures literally growing on an easel and spreading their way across the canvas. I learnt an awful lot about how to compose an image from that experience. Then I’ve always been very interested in visual art, so it is a fairly major influence. I often use the analogy of painting producing an image on a two dimensional surface, to producing an image within a three dimensional space with light. I frequently use that as a teaching tool.

CX: Because this is a technical magazine, do you have a favourite lighting fixture?

A good tungsten profile. If you’re doing 400 at a time, I still think you can’t beat an ETC Source Four Profile. If you are doing something that requires more optical quality, then a Niethammer or a Robert Juliat.

In theatre lighting, we bowerbird things from other industries. The humble Par Can, for example; there was a period of two decades where I was producing rigs full of the things, stolen, in order, from the rock and roll industry, who themselves stole it from car headlights. I think that’s the way that theatre has always worked.

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.