Subscribe to CX E-News

Snippets from the archives of a bygone era

When Lionel Richie sang over the top of his microphone at the 2011 Hunter Valley Bimbadgen Estate concert, he was barely audible, even from the pit where I was photographing him. And when his sound engineer drove the system into feedback trying to raise the volume, it brought back bitter memories of a problem I had to deal with some 28 years earlier, in 1983, during my Philippines sojourn.

The bane of every sound engineer’s life is trying to boost weak signals, and when confronted with complaints that a particular vocalist can’t be heard, it’s difficult to explain that the problem is often the vocalist’s microphone technique, their vocal technique, or both.

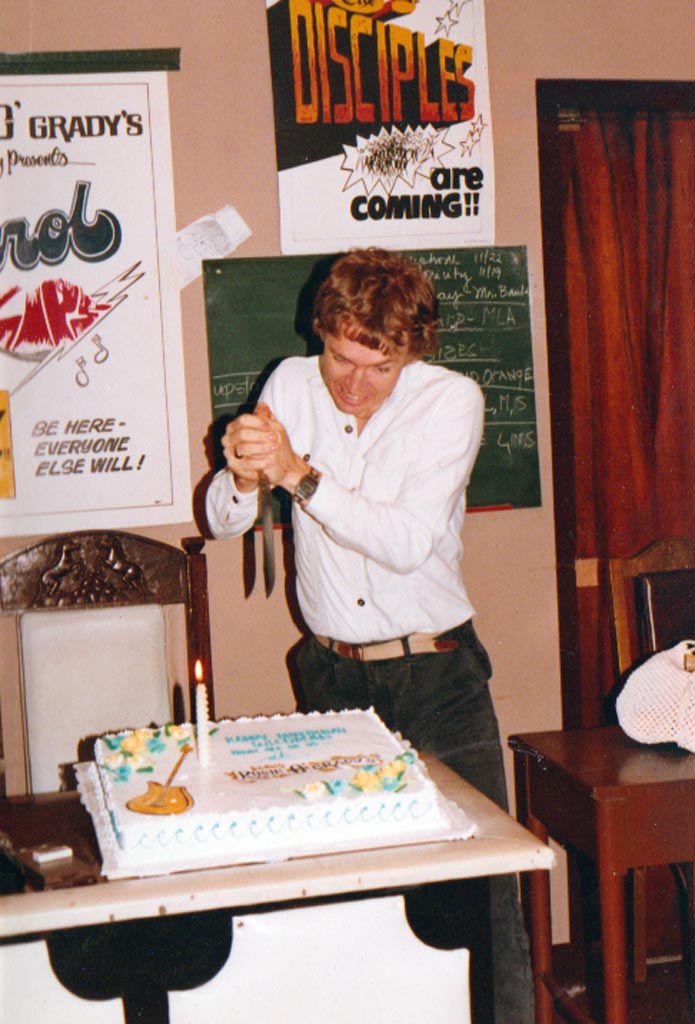

The Disciples were the second Filipino band that I booked into a residency at Rosie O’Grady’s, a venue that catered to US military personnel from the Clark Air Force Base north of Manila. I had several conversations with the lead singer, who not only had a faint voice but augmented the problem with poor microphone technique. When those conversations failed to produce a solution, I asked the band to replace him, and when they refused, I went looking for a new band.

Manila, some ninety kilometres south, was my hunting ground for new bands. Here, a wealth of talent could be found in venues ranging from five-star hotels to pizza parlours. I placed an ad in the Manila Bulletin newspaper and set up camp in a Manila hotel room. Additionally, I advertised for a piano player as a favour for a friend, a New Yorker, who wanted a pianist for his ritzy restaurant, The Manhattan Transfer.

There were, of course, no mobile phones in those days, so I took the unauthorised privilege of listing the hotel’s telephone number as my contact number; this failed to impress the reception desk staff when the calls started to pour in.

An early response to the ad came from a band that rehearsed inside the Villamor Air Base near the Manila International Airport (MIA).

Getting into the base wasn’t all that easy, as the Filipino military weren’t as welcoming as Filipinos in the tourist areas. It had only been a matter of months since the assassination of Benigno ‘Ninoy’ Aquino, President Marcos’ former opponent, at the neighbouring airport, and there was talk of revolution in the air.

I arrived at the gates of the air base with only the name of the Deputy Wing Commander, who eventually granted me access. After running the gauntlet of scowling Filipino military stationed around the base, I located the band rehearsing in what looked like a disused ammunition shed. Here, I was made to suffer through a repertoire of poorly performed cover songs. I then made my polite excuses and returned to the hotel to retrieve my phone messages from the disgruntled reception staff.

After a night on the town, I awoke the next morning with what I thought was my usual hangover. The air conditioner had iced and stalled, leaving only a noisy, ineffective ceiling fan that emitted one squeak per rotation.

I opened a window, which let in a miasma of rotting garbage and diesel fumes that seasoned the musty, humid room. Unable to relieve my heat stress, I realised that my condition was much worse than a hangover. I had a burning fever and other symptoms so severe that I phoned reception, asking them to arrange for a doctor to visit. Filipinos often struggle with the Australian accent, and the front desk thought a ‘doctuh’ was something I was trying to order from the room service menu. Eventually, I was able to communicate the message.

“Oh, you want a ‘doktor’, sir?”

Two female medical staff members soon arrived and took blood samples. They returned in the afternoon with the diagnosis: “It’s typhoid fever, sir.” I was really taken aback.

“Well, at least it’s not cholera,” I offered optimistically.

“Well, we didn’t check for that,” was the reply.

The medical staff wanted to admit me to the local hospital, but I’d seen Manila hospitals so devoid of funds that the paint blistered and peeled off the internal walls. I’d seen patients wheeled in on cane wheelchairs spattered with the previous patient’s blood. And in these theatres of massive overcrowding and declining morale, I’d seen doctors wearing sandals and jeans treating patients lying on stretchers in hallways, where IV bags were hung from window winders due to a lack of IV poles.

“No thanks; I’ll stay at the hotel.”

I was given injections and a profusion of medications so complex that I was issued with a chart so I could regulate the times and dosages. But in spite of all the mediations, my temperature continued to climb, sometimes to an unbearable high before I’d break out in a lather of sweat. In B-grade Hollywood movies, this was often followed by some elation because it signified the movie cliché that the fever had broken. Not so in real life, as the temperature starts to build again, and this is repeated over and over. Along with the high fever and bodily dysfunctions, typhoid toxaemia can also cause a temporary state of acute psychosis.

The incessant ringing of the phone was akin to the drums that often drove our Hollywood heroes stricken with jungle fever to the brink. I don’t remember any of the telephone conversations I had, only that they all seemed to be inquiries from piano players and not bands, and I presumed that my conversations would have been nonsensical.

On the third night of my hotel quarantine, a cacophony of loud voices, breaking glass and other metallic resonances awoke me. In my delirium, I thought the revolution had begun, and I wondered how I would be treated by the rebels after their impending invasion of the hotel. However, after the melee, there was an eerie silence, and I fell back into a deep slumber.

The next morning, against medical advice, I decided to vacate the hotel, and I wondered if the hotel staff would try to prohibit my departure. I knew the exact time the bus left from directly outside the hotel, so I planned my escape. I paid my bill at the front desk to a receptionist who seemed oblivious to my internment paranoia, so I coyly asked, “What was all that commotion last night?”

“Oh, that was just the garbage collectors, sir. They’re very noisy.” Somewhat bemused, I boarded the bus, and as it steered out into the Manila traffic, I pondered, “All this trouble over a singer with poor microphone technique?”

At Rosie O’Grady’s, I informed my employer that I was unable to find a replacement band. A week later, while dining at The Manhattan Transfer, I began apologising to my friend for not finding a piano player for his restaurant. To my amazement, he told me that I had put him in touch with a very good pianist who was now in his employ.

Some two and a half years later, in February 1986, I was again driving down to Manila in search of new talent when I took a wrong turn and ended up stuck in a sea of yellow ribbons and placards in the middle of the most massive protest I had ever seen. This was the now- famous civil disobedience protest at Luneta Park, which attracted an estimated two million people in support of Corazon ‘Cory’ Aquino.

The event was organised to decry Ferdinand Marcos’ alleged rigging of the snap election, which Corazon Aquino had contested and lost despite overwhelming support after the assassination of her husband.

Girls with yellow ribbons in their hair were collecting donations, so I called them over and donated.

“Do you like Cory, sir?” they asked. “Yes, I do, but how do I get out of here?”

The girls then called over some macho guys, who cleared a passage for me to turn around and exit the traffic jam.

Some 10 days later, I joined a huge crowd just a short walk from my rented house in northern Luzon to watch the tanks roll down MacArthur Highway en route to Manila for the 1986 People Power Revolution, which rightfully installed Cory Aquino as the 11th President of the Philippines.

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.