Control

26 Feb 2021

Total Control

Subscribe to CX E-News

Hey good CX folks, in case world events have you a little distracted, it’s summer again. Depending on where you live and how locked down you are, sun, sand and surf might be a little out of your reach right now.

By choice, I am staying in the mountains where summer means fire. As part of that, I’d like to delve into some of the operational structures, facilities and resources that emergency services (and CFA in particular) use to control urgent events like fires.

Control, command & coordination

Where I live, Emergency Management Victoria (EMV) is responsible for coordinating agencies and their resources during emergencies. To do this they use a system of six Cs:

Control – The overall direction of response activities in an emergency, operating horizontally across agencies.

Command – The internal direction of personnel and resources of an agency, operating vertically within the agency.

Coordination – The bringing together of agencies and resources to ensure effective preparation for, response to and recovery from emergencies.

Consequences – The management of the effect of emergencies on individuals, the community, infrastructure and the environment.

Communication – The engagement and provision of information across agencies and proactively with the community to prepare for, respond to and recover from emergencies.

Community Connection – The understanding of and connecting with trusted networks, trusted leaders and all communities to support resilience and decision making.

Victoria’s Country Fire Authority (CFA) follows these guidelines so that their response meshes easily with other agencies like Police (VicPol), State Emergency Service (SES) and the like.

Lines of command & control

As with the rest of EMV, CFA has a chain of command in its control structure, called the “line-of-control”.

Initially, the crew leader on the first arriving appliance becomes the Incident Controller (IC) and runs the show onsite – they assess what is happening on the ground before making decisions and directing resources.

If they and their assigned teams can mop it up with the hardware and people at hand or in transit, great. If not, and the situation deteriorates, control may be passed to an Incident Control Centre (ICC), which is often aligned with a District Command Centre (DCC).

Next up the line of control is the Regional and then State Control Centres. By the time an incident gets to these facilities it is large and complex (like last summer’s fires).

When the ICCs are not in play, a “line of command” is used.

Here, the fireground IC reports to the Rostered Duty Officer (RDO – situated at the DCC). The RDO is responsible to the Regional Agency Commander (who reports to the Regional Controller) but also to the State Duty Officer (who reports to the State Agency Commander).

It’s onerous stuff, but a follows a well-tested and well-known set of procedures.

Earlier this week, we had a local fire that was resolved on site. The first tanker on scene couldn’t initially gain access, so a local Deputy Group Officer (DGO) in a private vehicle set the scene (as IC) and then handed off control of the job to a Group Officer (GO) when they turned up.

This job all ran smoothly and was easily quelled with six tankers in an hour or so. When things quietened down and it was clean up time, control was passed from the GO to Captain of the brigade remaining on scene.

If it was looking likely that it would take off or get too tricky, the job would have been escalated to the DCC (which was staffed and on standby as it was a Total Fire Ban day).

On a non-TFB day, a nearby Local Command Facility (LCF – located in each Group HQ) would be contacted and prepared in case we needed some offsite coordination. They are also used to spread the load when there are multiple incidents running in a district.

Fortunately, none of that was required in this instance.

When the heat is on, it’s re-assuring to have pre-defined processes to follow. It can get pretty difficult maintaining clear thinking when you are surrounded by noisy trucks, whining pumps, low-buzzing aircraft and radios squawking everywhere.

Not to mention being hyper aware of the visceral physical threat of nearby flames that you often cannot see for the smoke.

Like most emergency organisations, CFA has many pre-defined procedures and methodologies, outlined in Standard Operating Procedures (SOP). For example, “SOP J03.15 – Transfer of Control and IMT relocation, outlines the process for the transfer of control from the field-based Incident Controller to an ICC based Incident Controller.”

Control centres – what tech keeps us safe?

Control centres vary in their technical setups. Out in the field, we use a combination of digital VHF and analog UHF radios. Each appliance has a VHF link to talk to the state dispatch centre.

We carry additional portable VHF units that can be switched to a discrete fire-ground channel for the IC to communicate directly with tankers, aircraft and other appliances or crew on scene.

Forward Control and Field Operations Vehicles can also be deployed to provide extra radio and trunking facilities and are often used as control points on scene.

UHF radios are used for truck-to-truck comms and are particularly handy in our area, where we often lose VHF links. And don’t even get me started on our crap phone coverage …

An LCF will typically have multiple VHF radios and workstations, with reliable internet, landline phone connections and yes, faxes. DCCs and ICCs take it a step further and have dedicated spaces for many people.

I visited our local (District 22) ICC recently and took a good look around.

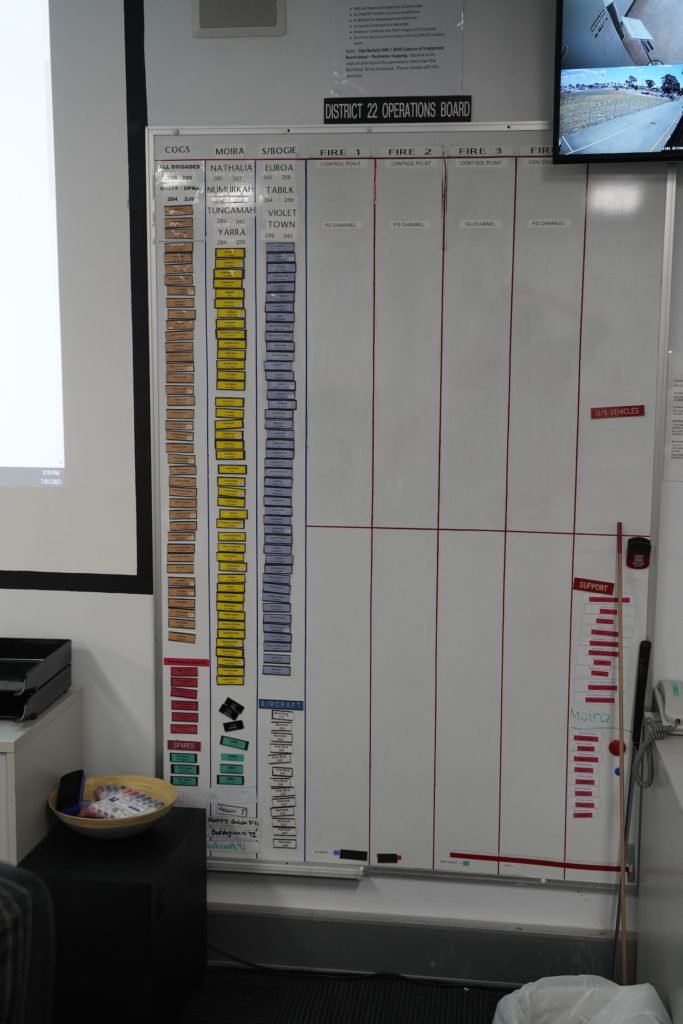

Gear-wise, six Tait digital VHF radios are rack mounted, and these feed several RU of Omnitronics radio management modules which then distribute comms to and from the DCC and ICC rooms.

Pretty much everything else is IT-based, from intelligence gathering to analysis. Given the critical nature of emergency response, the server and communications room equipment have a backup generator always ready to go.

Apparently, this one has been required more than once.

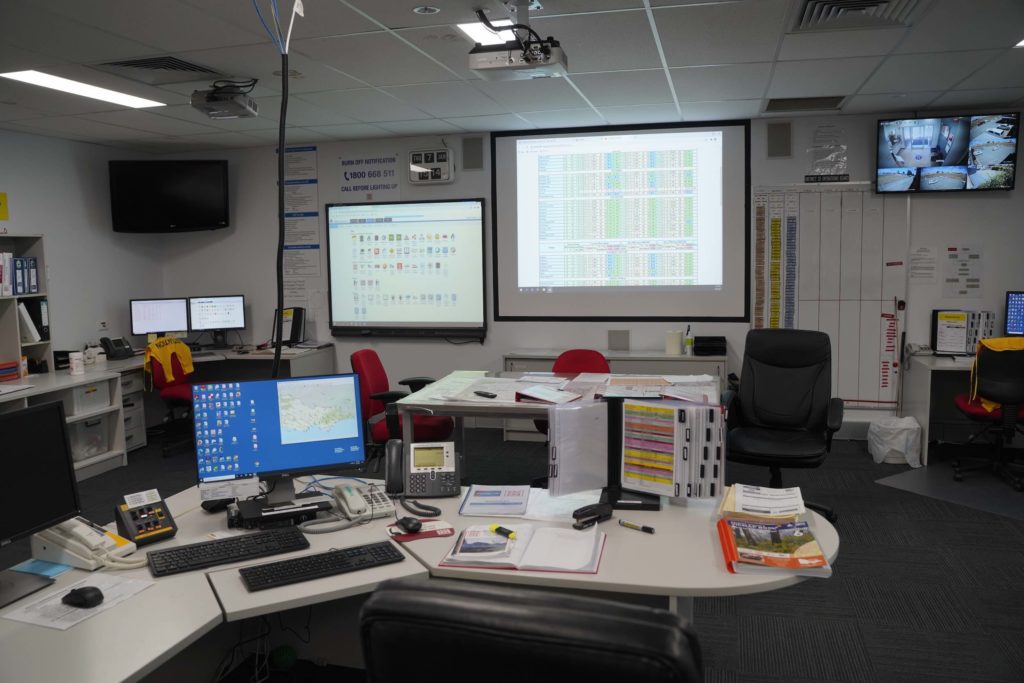

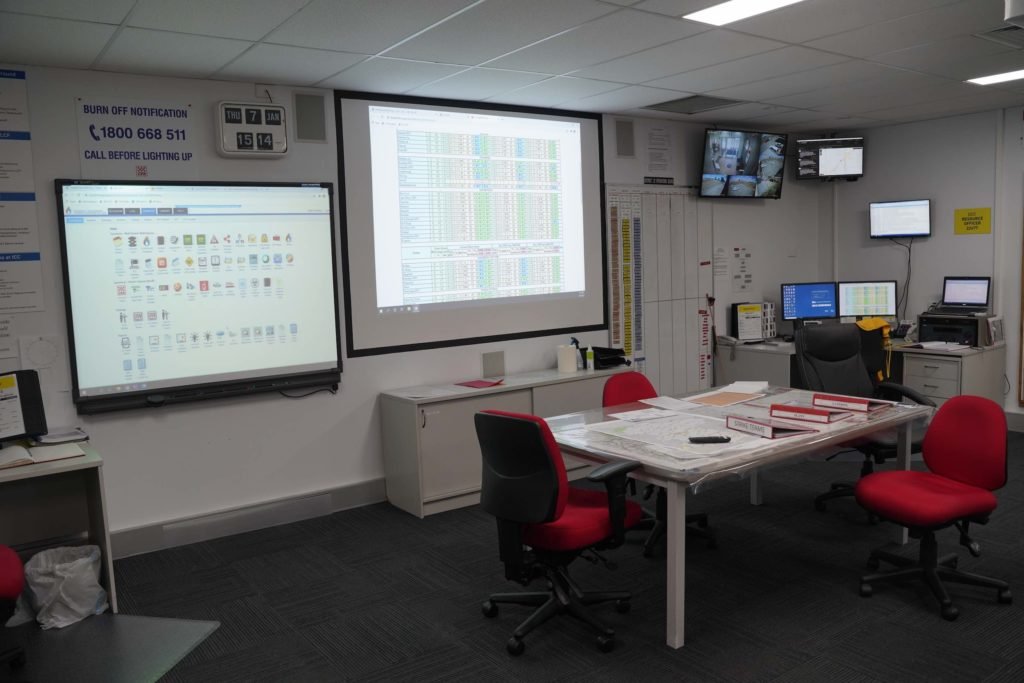

Surprisingly, the control rooms don’t carry much high-tech AV equipment. Each has a couple of projectors and some intelligent whiteboards (which are mainly used as extra screens).

The projectors get a fair workout and each workstation has the requisite PC but old school magnetised whiteboards and maps on a table are still used heavily.

When emergencies are escalated to an ICC or higher, an Incident Management Team (IMT) is assembled. Depending on the complexity of the job, the IC will often assign roles in Intelligence, Control, Operations, Logistics, Planning, Finance and Catering.

At D22 DCC, the first four have their own workstations situated around the RDO. If they assign a job to the ICC, the workspace is much larger, with multiple workstations in a larger area and dedicated rooms off the side for Control, Comms, etc.

Work areas within the D22 District Command Centre

Why so low tech in 2021?

Many of the information sources are IT-based and the state servers are where the heavy grunt work is done. Resource Tracking System (RTS), Emergency Management-Common Operating Picture (EM-COP), State Air Desk (SAD) and Computer Aided Dispatch (CAD) are all accessed via the secure CFA WAN.

Weather and analytical tools also come down the IP tube. These are all easily routed to the projectors or PCs. Comms to the field are conducted on tried and tested RF. The aircraft comms gets particularly noisy but are vital to effective fire suppression.

Whatever their failings, the old school methods do still work, and everyone can understand it without needing a training session on how to drive a new gizmo every week.

Professionally, I’d love to see more tech in there, but I do understand the organisation’s cultural and budgetary constraints. It’s a big institution with a lot of ongoing demands for infrastructure, equipment and staffing requirements.

What does this mean for CX readers?

Emergency services organisations are always reviewing and upgrading their systems. As highlighted above, there are opportunities for AV integrators to update and maintain existing setups.

For the adventurous, there is some prospect to propose newer approaches to your district or regional centre. How much traction you’d get is another matter and large bureaucracies do move slowly. Budget limits are always an issue but, when they do upgrade, it will likely be major.

Install opportunities might be a slow-burn affair but are worth it when they come up. Keep an eye on the tender pages.

Some of the structures and approaches outlined above might also be handy for your organisation. I can see many parallels with live production work and emergency management, not the least of which are learning to stay calm and make time critical decisions under great pressure.

If you live in a rural or peri-urban area, perhaps consider joining as a volunteer with a local emergency service. You can get to practice your C & C skills in real-time and maybe even get some joy from giving to your community, both locally and wider.

You won’t have to sell your soul to get some basic control here…

Disclaimer: The views above are entirely my own opinion and are not the official position of the CFA or any other related agency.

CX Magazine – February 2021

LIGHTING | AUDIO | VIDEO | STAGING | INTEGRATION

Entertainment technology news and issues for Australia and New Zealand

– in print and free online www.cxnetwork.com.au

© VCS Creative Publishing

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.