THE GAFFA TAPES

21 Jun 2024

Turning Fact into Fiction: NEON PROVINCE

Subscribe to CX E-News

Snippets from the archives of a bygone era

In 1980, I enrolled in a series of scriptwriting workshops hosted by WEA (Workers’ Educational Association), which focused on writing for television. The adult education course was primarily attended by aspiring writers from Sydney’s elite of the upper north shore and the eastern suburbs, whose preferred genre was akin to English playwright Noel Coward’s sophisticated parodies or Agatha Christie’s short stories and crime novels. These were not genres that I was enamoured with, and comedy such as that of Paul Hogan was largely frowned upon and thought to be crass and humourless. Thus, I fell afoul of my fellow students when I suggested that if they didn’t get a laugh out of ‘Hoges’ drying his underpants in a vertical griller, they had no sense of humour.

My writer’s block began immediately after the WEA course, and it wasn’t until three years later that I found my muse in the most bizarre array of characters during my tenure in sound, lighting, and band management in American nightclubs off the US Clark Air Base in the Philippines. Here, in the barangay of Balibago, all the visuals were laid out in the best mise en scène any writer or film director could hope for, and from the moment I set foot in the town, it was as though I had strayed onto a movie set.

Along with the vista of patrolling military vehicles was a large contingent of the 8,000 GIs stationed on the base who bar-hopped the hundreds of neon-lit bars that dotted the streets. There were also three fledgling nightclubs that would gradually morph into live rock ‘n’ roll venues, and over a four-year period, I worked for all of them. These and other clubs were owned and operated by a mishmash of expatriate characters, some colourful, some eccentric, some violent, and all feuding as they aggressively vied for the lucrative US patronage, without which they would face certain closure. However, they managed a delicate and often troubled accord with the US air base, knowing that they would be put off-limits in a heartbeat if they strayed from stringent US stipulations.

Upon my return to Australia in 1986, I believed I had all the ingredients needed to make a fictional movie, and I began to piece together a screenplay about a character involved in the music and entertainment industry who becomes stranded in the Philippines.

Destitute, he is forced to supervise the installation of sound and lighting and manage the entertainment in a troubled nightclub catering to US servicemen from a nearby air base. His expertise projects the nightclub to a prominence that earns the ire of a violent rival nightclub owner, Clayton McCoy, and when he becomes infatuated with McCoy’s girlfriend, the clubs erupt into a deadly feud.

I toyed with different ways to strand my protagonist in the Philippines in the 1980s.

By chance, after sitting for some time in a grounded airplane on the tarmac at Sydney Airport, with the pilot being denied permission to take off because of a faulty LED light, I realised that it was plausible that something as diminutive as an LED light could alter an entire sequence of events.

So, in the script, Myles Becker, an entertainment industry specialist who is en-route to a trade show in Las Vegas, becomes stranded in the Philippines when his plane is forced to land in Manila because of a faulty LED light. Following an alcohol-fuelled night on the town, his wallet and passport are stolen.

He is left destitute, and his only recourse is to accept an offer by an English expatriate, Billy Watson, to manage the entertainment at a troubled American nightclub, Kathmandu, in the coastal town of Barrio Del Mar, which caters to personnel from a US military base.

This is where fact and fiction become blurred, as there is no such place as Barrio Del Mar in the Philippines, nor was the Clark Air Base located on the coast. But I have always had a fascination with coastal regions, and in 1989, when I travelled to the coastal town of Vũng Tàu in Vietnam, I found my ideal location. Now I could have my protagonist’s romantic interest, Leah, wandering disillusioned, barefoot, and windswept through French doors onto the beachfront, her chiffon dress and hair wafting in the night breeze while she carries a half-empty bottle of rum hung from one hand and sips from a half-filled glass with the other.

The fictional club, Kathmandu, was, in fact, the name of the original club that I was contracted to work for in 1983; however, the lack of finance caused long delays in construction, and it became satirically known around town as Kathman-don’t and alternatively opened under the name of The Paradise Club.

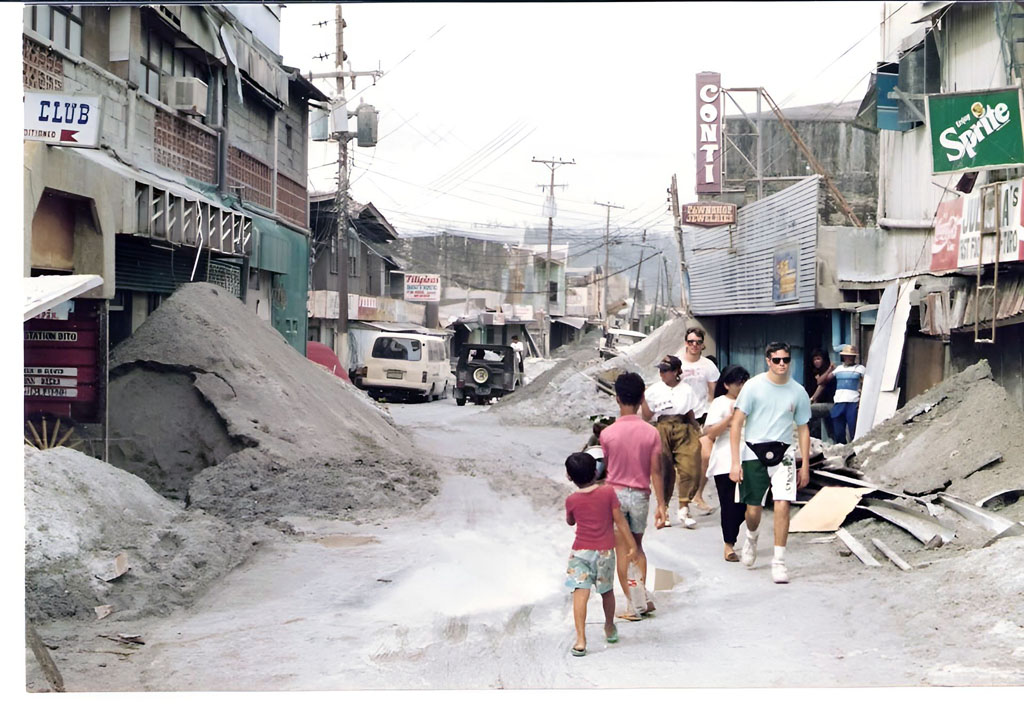

I needed a catchy opening scene, and it was the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, which was just 14 kilometres from the Clark Air Base, that delivered it. The eruption not only caused the entire base to permanently evacuate, but the ash that descended on the bars and nightclubs caused a large contingent of them to either collapse or close down. However, one bar owner decided to add buffoonery to the disaster when he set up a kind of beach resort in the ash on the roof of his club. Clutching a bottle of Bourbon while embracing his girlfriend, he refused all attempts by authorities to be coaxed down.

In the script, the eruption of the volcano is replaced with a devastating typhoon that causes windswept sand to mound onto the roof of Kathmandu, where Becker is employed. It’s the last straw for Becker’s employer, Jim Cassidy, whose nightclub has been placed off-limits by the US base after being partially destroyed when bombed by McCoy’s goons. So, Cassidy, drunk and in a deranged state of mind, takes his girlfriend up onto the roof of his nightclub during the typhoon and resists all attempts by the local police to coax him down.

“Why would I want to leave here? I’ve got the best beach resort in town; I’ve got a fine lady here, and the best bottle of Bourbon that good old US dollars can buy,” says Cassidy.

In reality, Typhoon Yunya did follow the disastrous Mount Pinatubo eruption, soaking the ash that piled on the rooftops, and the combination of strong winds and earthquakes that followed collapsed thousands of buildings.

In the script, the typhoon whips the nightclub’s damaged neon signage, slamming it back and forth against the building’s facade as it swings precariously from its electrical cabling. The scene dissolves to a former era when the nightclub stands resplendent and is undergoing renovations while Cassidy ponders replacing his incompetent entertainment manager. The stage is set for Becker to enter.

While drafting my script, I joined the Australian Writer’s Guild and spent years writing, polishing, and sending it to a plethora of producers, film companies, and agencies, and I’ve got all the rejection letters to attest to that. Finally, the reality set in that the industry doesn’t accept unsolicited scripts.

I decided to adapt the screenplay to a novel, but it wasn’t an easy task, and it took a number of years. Of course, the narrative is fictional, but I was meticulous about preserving the zeitgeist of those heady days so it would represent a snapshot of the era. A lot of the dialogue is derived from bizarre oratory that I heard from an assortment of characters; however, individual traits from a number of real characters have been reshaped and correlated to form fictional characters.

The book, Neon Province, wasn’t completed until 2021. I sent the synopsis and sometimes several pages, as was the stipulation, out to any publisher who feigned interest in reading unsolicited scripts. But unsolicited literary works aren’t accepted; they seem to be held in some sort of pending file as a pretence to reading them, and then the rejection letter follows. So, the only remaining avenue was to self-publish. Surprisingly, Amazon does this for free; you just pay a discounted fee for any copies you wish to purchase, and there is no print minimum. This works out cheaper than going directly to a printer, and along with the printed copies, you have a slim chance of a sale amidst Amazon’s 3.2 million titles.

It wasn’t until a couple of months ago that my bank sent me a letter notifying me of suspicious activity because of two overseas deposits in my account, one of 49 cents and another of 43 cents. However, these were royalties from Amazon; it seems I had sold two copies of my book.

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.